"The Voice of the Steel City"

The Story of

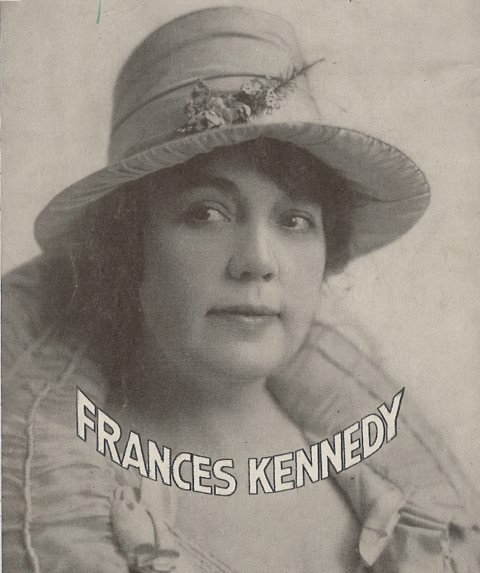

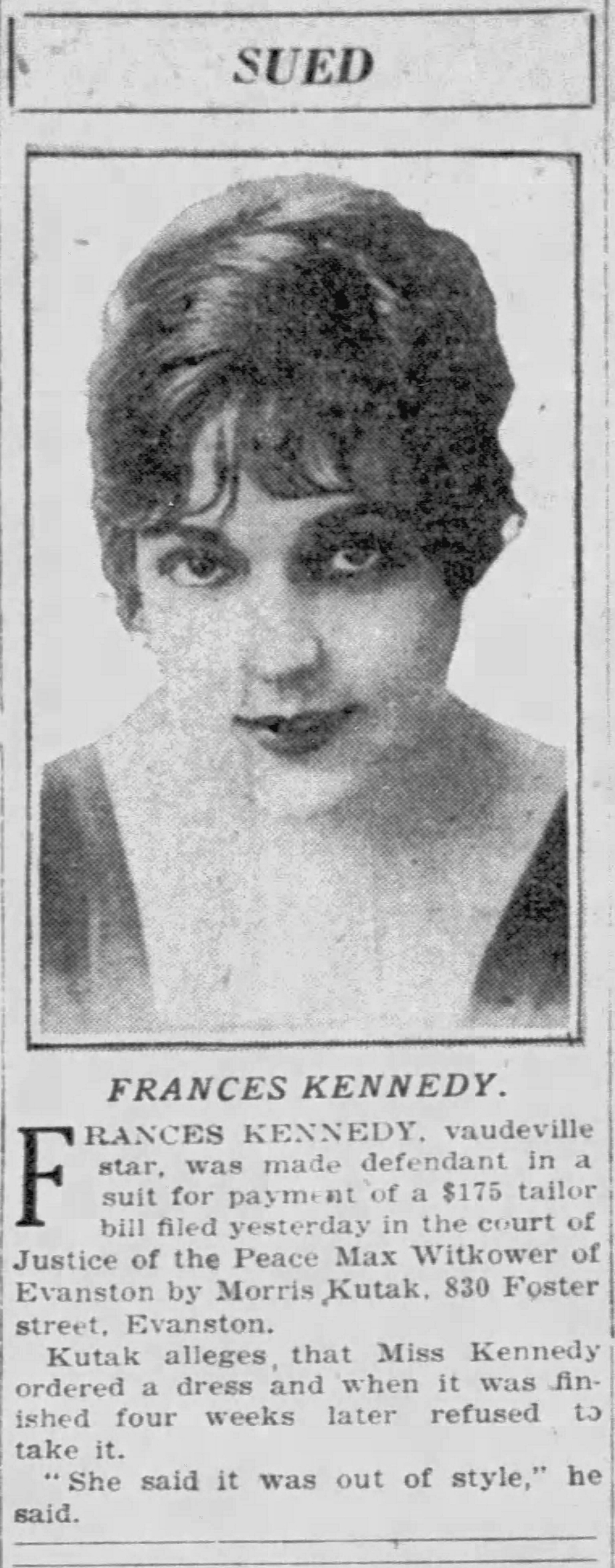

Miss Frances Kennedy

"The Merriest Comedienne"

The second part of the story of

Gay Mill Gardens.

For a detailed look at the musical comedies Frances performed in see

"Sing, Sing, You Tetrazzini, You"

When Frances Kennedy and her husband brought Gay Mill to Miller Beach she was a veteran of almost two decades of musical comedy and vaudeville,

and she wasn’t done.

She loved entertaining people from the stage as much as she loved her family.

She hasn’t been written about in books; she was one of some 12,000 vaudevillians on stage in 1920. For 30 years from musical comedy to vaudeville she was widely known among those who loved the popular theater. This is a glimpse into her career, which also included launching the region's first radio station, WJKS, "Where Joy Kills Sorrow."

As a young 20 year old switchboard operator who had sung solos in her church choir since she was 10 she had her eyes on the stage.

No doubt preforming in local and school theater at a young age, likely her first professional experience was with the Ziegfeld

company of Anna Held’s

(Footnote:

Anna Held, the five foot tall common law wife of Florenz Ziegfeld, was one of the most well-known stage performers of the

fin de siècle and into the twentieth century.Wikipedia article on Anna Held.

) Mam’selle Napoleon, a musical in five acts that had a huge cast, some 80 to 100 people including the chorus,

of which Frances was a member. When she joined production isn’t known except that when its tour finally ended in Chicago on June 4, 1904

the paper said she had been with the company for a year and a half, which, if true, she had joined when Mam’selle Napoleon

opened October 28, 1903 in Philadelphia

(Footnote:

Advertisement, The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 28, 1903, page 7. “TO-NIGHT / FIRST TIME ON ANY STAGE”

)

when she was 25. The show toured extensively in the east before going west: among many other stops were

Minneapolis – Butte, Montana - Seattle – San Francisco – Los Angeles – Salt Lake City

and finally to Chicago in a five car special train that set a speed record at the end from Omaha to Chicago.

(Footnote:

“Rock Island Makes Record,” Chicago Daily Herald, June 17, 1904, and others. “The Rock Island has established a new record for fast time between Omaha and Chicago.

May 22nd, a special train of five cars, carrying the Anna Held Company, left Omaha at 1 a. m., arriving at Chicago at 12 o’clock noon.”

)

Mam’selle Napoleon closed June 4th at the Illinois Theater after 7 months and a week. Frances Kennedy was off and running on a career

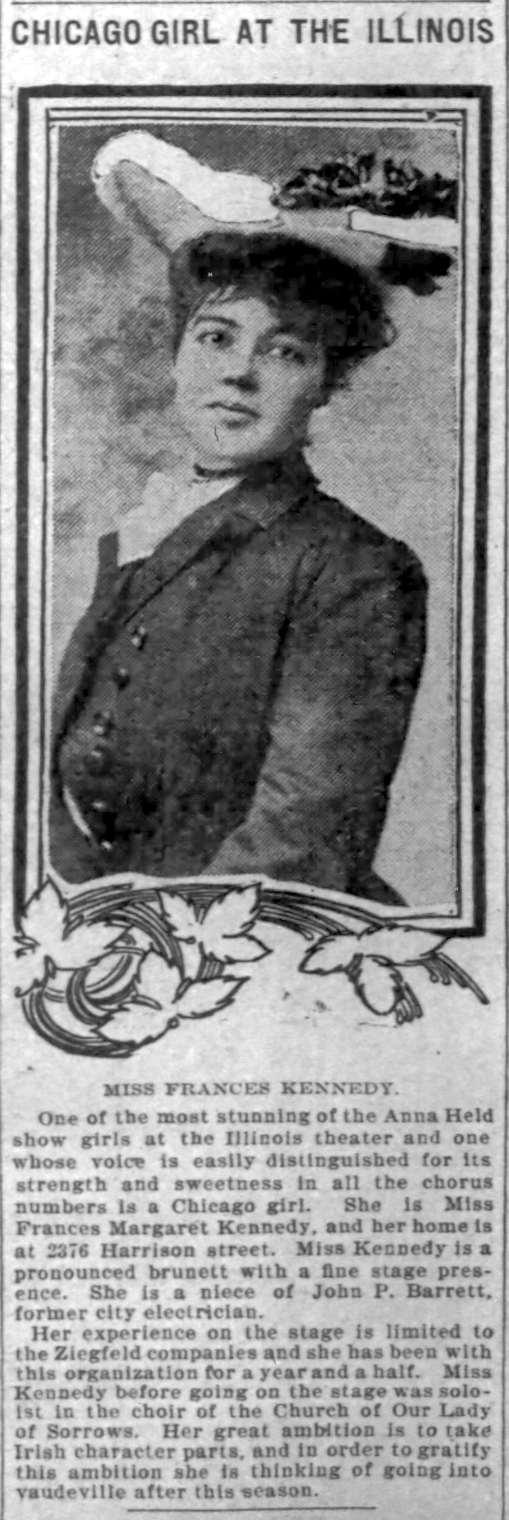

that would incorporate that kind of travel. The Chicago Inter Ocean noticed her and ran her picture, calling her one of the "most stunning of the Anna Held show girls."

of which Frances was a member. When she joined production isn’t known except that when its tour finally ended in Chicago on June 4, 1904

the paper said she had been with the company for a year and a half, which, if true, she had joined when Mam’selle Napoleon

opened October 28, 1903 in Philadelphia

(Footnote:

Advertisement, The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 28, 1903, page 7. “TO-NIGHT / FIRST TIME ON ANY STAGE”

)

when she was 25. The show toured extensively in the east before going west: among many other stops were

Minneapolis – Butte, Montana - Seattle – San Francisco – Los Angeles – Salt Lake City

and finally to Chicago in a five car special train that set a speed record at the end from Omaha to Chicago.

(Footnote:

“Rock Island Makes Record,” Chicago Daily Herald, June 17, 1904, and others. “The Rock Island has established a new record for fast time between Omaha and Chicago.

May 22nd, a special train of five cars, carrying the Anna Held Company, left Omaha at 1 a. m., arriving at Chicago at 12 o’clock noon.”

)

Mam’selle Napoleon closed June 4th at the Illinois Theater after 7 months and a week. Frances Kennedy was off and running on a career

that would incorporate that kind of travel. The Chicago Inter Ocean noticed her and ran her picture, calling her one of the "most stunning of the Anna Held show girls."

Following the final performance of Mam'selle the Illinois theater had a short run of Richard Carle's The Tenderfoot and that was followed by The Forbidden Land by the Dearborn company which Frances joined becoming one of the "Tibetan Ladies," Motema. Forbidden Land ran for 6 weeks in July and August of 1904, after which she joined the company at the 700 seat La Salle Theater where she would stay for nearly two years performing in 5 plays, slowing working her way up in the casts and in attention in the papers.

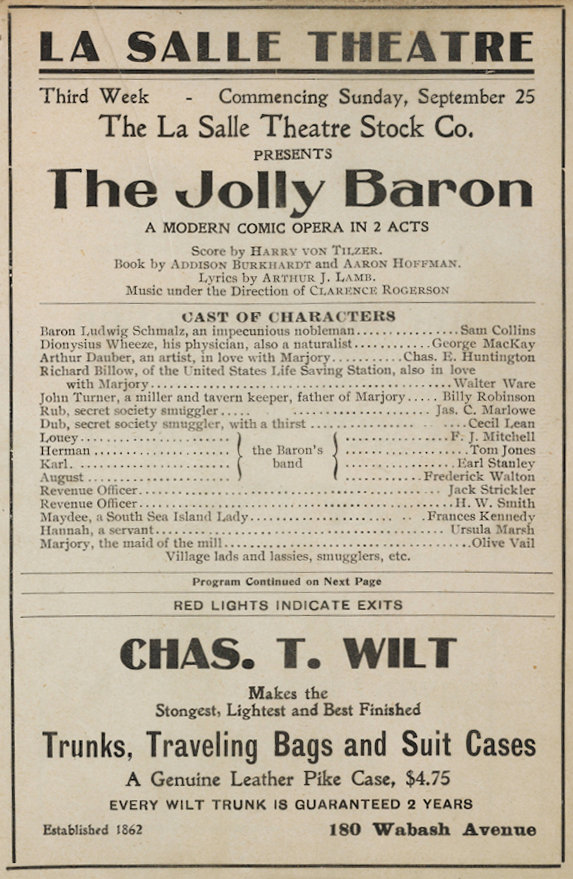

- The Jolly Baron ran for 2 months in the fall of 1904, closing after a hundred performances, in which she played “Maydee, a handsome and graceful South Sea Islander.” The Chicago Inter Ocean pictured her and gave her a great review for her singing of the song "Maydee." (Footnote: Chicago Tribune, September 15. )(Footnote: "News of the Theaters," Chicago Inter Ocean, September 14, 1904, page 5. )

- On November 21 she opened in His Highness the Bey which ran for 5 months followed by a short tour to a few Illinois theaters. The week before Christmas she introduced a new song into the show - "Julie Dooley" was well received.(Footnote: "Playbills," Chicago Tribune, December 25, 1904, page 15. )

- The Isle of Bong Bong ran for 3 months beginning on March 15, 1905, closing June 17th. Four days after the closing she married Tom Johnson,

a $890.00 a year

(Footnote:

American Almanac, Year-book, Cyclopedia and Atlas, Volume 2; Google Books. ($24,665 in 2017 money.)

)

assistant prosecuting attorney in the City of Chicago law offices who was prosecuting arson cases.

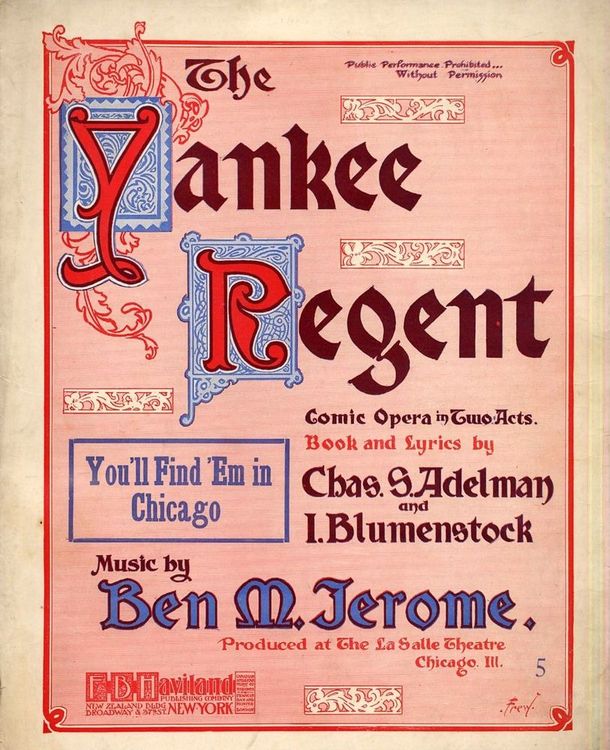

- After a short honeymoon to Mackinac Island she opened in The Yankee Regent at the La Salle on August 12, a play that ran over 150 performances until the first day of December. She played Henriette Craig, an American millionairess.

- The next day, December 2nd she opened in The Umpire, a play that proved to be a success, running 304 performances to June of 1906 setting a record for the longest running play in Chicago history when it hit 204 performances in April.(Footnote: "Some Long Runs in Chicago Houses," Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1906, page 79. ) It was the story of a Chicago baseball umpire who fled for his life to Morocco after a bad call and featured a song called "The Umpire is a Most Unhappy Man." Frances left the cast several weeks before its closing, being about 5 months pregnant with Thomas junior who was born August 5th.

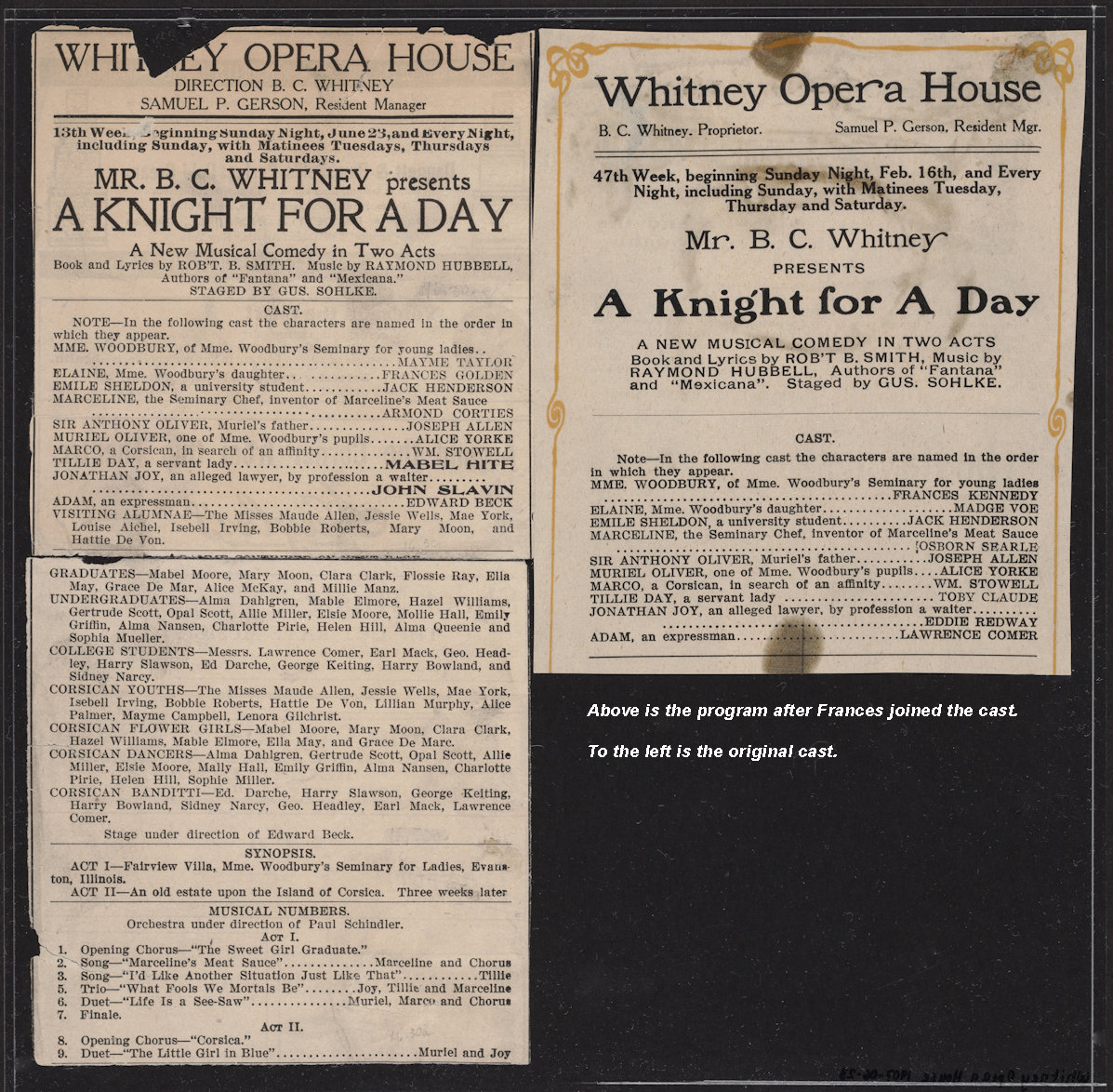

Frances took a year off to have Tom junior, but headed back to the stage on July 28, 1907 joining the cast of A Knight for a Day which had opened at the “new” Whitney theater in March. It ran through the winter until February 29, 1908 with over 500 performances.

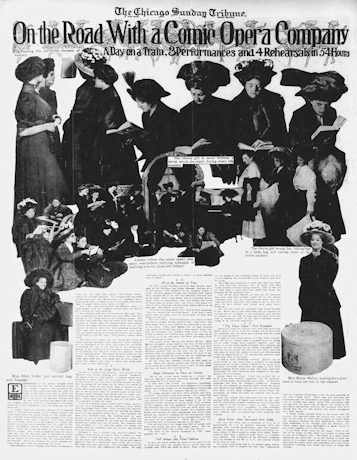

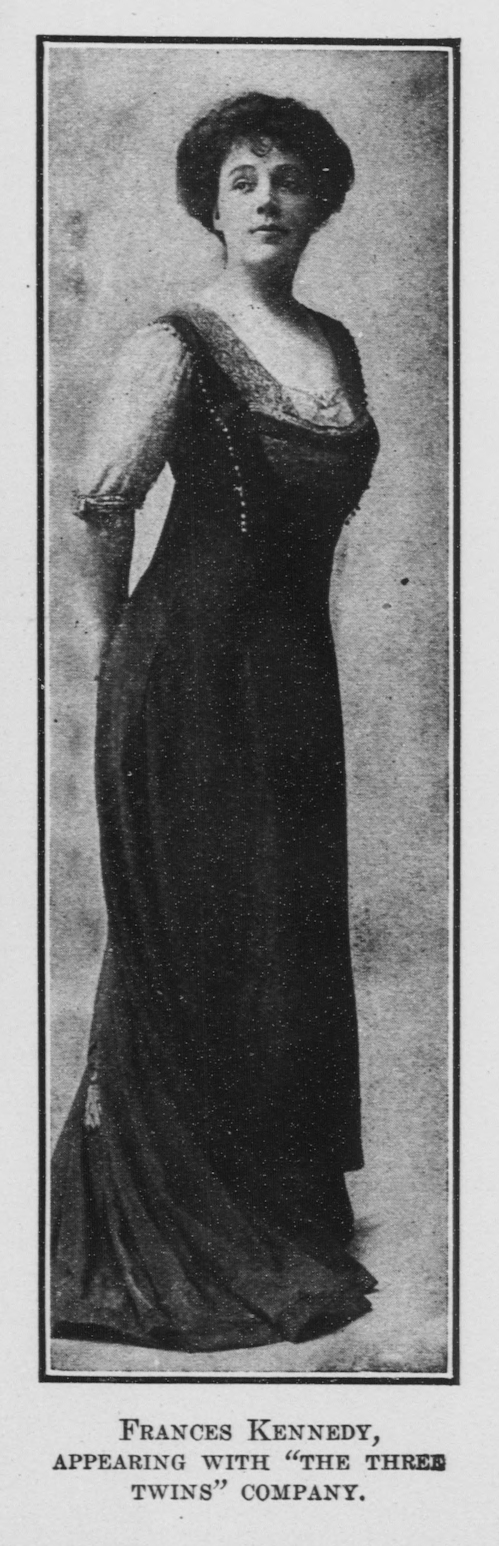

No rest for the stage struck: a week later, on March 7th she opened with the cast of The Three Twins at the Whitney opera house, but not before an out of town trial in Peoria. “On the Road With a Comic Opera Company” was a delightful, full page write up in the Chicago Sunday Tribune a month later detailing what a theater company goes through taking a show on the road for its first performance. The Three Twins turned out to be a huge success, playing for over a year, first in Chicago and then New York where it moved to in June of 1908. The play went on the road playing extensively in Wisconsin and other places in the Midwest in 1909, getting recognition in the papers. The popular song "Cuddle Up a Little Closer, Lovey Mine" came out of that show, recorded and used in films for years.

While it wasn’t playing in California in February of 1909, the Los Angeles Herald published Frances’ picture in its February 14th Sunday Magazine. (Footnote: For Frances’ engagements on Broadway (only) see the Internet Broadway Database (IBDB) ) Frances was still with the cast until the end of March, 1909, but the play continued in New York through that year and into 1910; it was quite popular. Frances must have left the cast following that Brooklyn engagement for at the end of June she opened in Chicago in The Tenderfoot, a revival from a few years previous that was a Richard Carle production. (Footnote: Richard Carle (1871-1941) wrote, directed and starred in The Tenderfoot. Frances would work with him again in Jumping Jupiter in 1910. Carle was a prolific sage and film actor with many credits: Wikipedia article on Carle. )

The Tenderfoot had a short run at the Colonial, opening on June 30th and closing July 24th, but Frances was noticed: “A season in the east with the 'Three Twins' company has had a beneficial effect on Miss Kennedy’s acting,. Although she is more sylphlike than when last she appeared at the Whitney, her stature as a comedienne has increased perceptibly,” wrote a reviewer in the Chicago Tribune. (Footnote: “In the Theaters,” Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1909, page 10. ) Within two months Frances would be back in New York rehearsing in the Shubert’s management of The Belle of Brittany with star comedian Frank Daniels. When The Belle of Brittany scored “…a decided hit at the Queen’s Theater, London…” the Shubert’s brought the play to New York, and Frances got the part of Madame Poquelin. (Footnote: Frank Daniels was a popular comedian and stage actor. His picture is at the Wikipedia article on Daniels ) It opened at the Daly’s Theatre on Broadway on November 8th and ran 72 performances before closing and going on the road on January 8, 1910. (Footnote: Internet Broadway Database: IBDB Broadway performances ) With no understudy she was unable to return to Chicago when her mother, Sarah Kennedy, died on the 20th. (Footnote: Chicago Tribune, January 21, page 8. ) The tour went to Shubert theaters in Connecticut - Buffalo - Detroit - Olathe, Kansas - Kansas City, St. Louis - Indianapolis - Cincinnati, where it ended its tour at the Lyric in April, with the word that Frank Daniels intended to continue the play the next season, which he did, but without Frances.

By August of 1910 she was back on the stage in Jumping Jupiter at the Cort Theater in Chicago with Richard Carle, with whom she had worked in his revival of The Tenderfoot.

Jumping Jupiter opened August 13 with Frances playing Genevieve Buchanan, the Major’s wife, but left to join the “road cast” of The Chocolate Soldier, an Oscar Strauss adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man which was enjoying an enormous success on Broadway. (Footnote: IBDB, IBDB ; Wikipedia. The Chocolate Soldier was revived on stage a number of times over the years, made into a silent film in 1914, and then films in 1941 starring Nelson Eddy and in 1955 starring Eddie Albert. ) The road cast of The Chocolate Soldier opened at the Garrick September 26th and Frances joined the cast October 11th The next year, when the play was on tour, a reporter for the Topeka, Kansas State Journal interviewed her and discovered that Frances, while rehearsing her part as Aurelia in Westchester, New York in October, had begun collecting Monarch butterflies. She brought them inside, filling her cottage in Westchester, New York with them by feeding them sugared water. (Footnote: “Frances Kennedy’s Remarkable Pets,” Topeka (KS) State Journal, Feb 11,1911, page 8. )

A Woman's Honor - or a husband's jealousy.

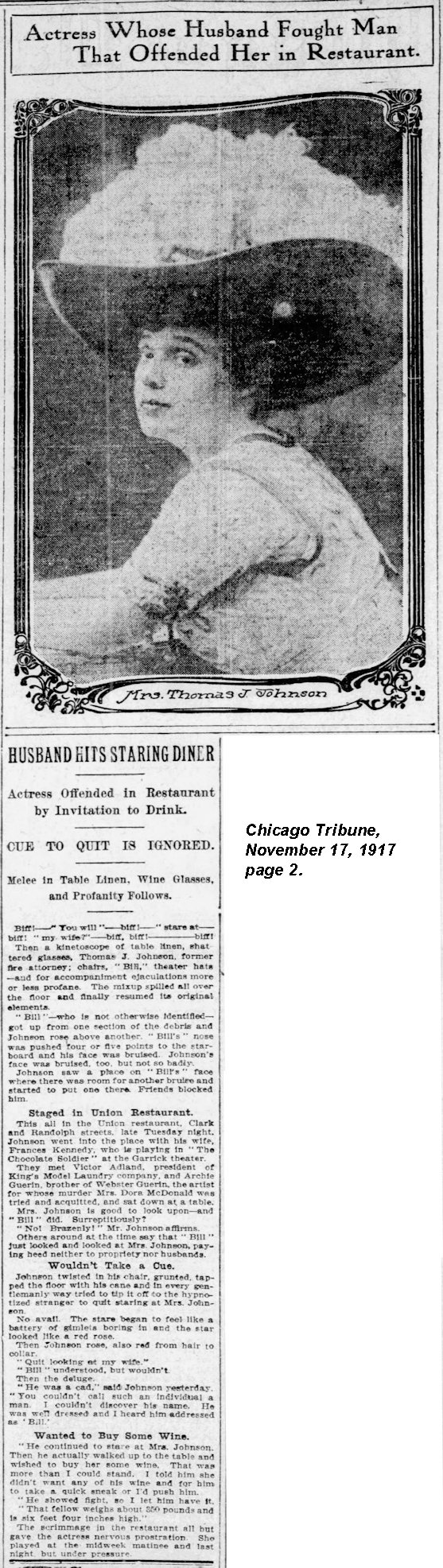

In November of 1910 Frances, and her husband, made the headlines, not for theater, but for a woman’s honor, or a husband’s jealousy. After a performance of The Chocolate Soldier, Frances, her husband, and two other couples were at the Union restaurant, Clark and Randolph Streets, when another patron began staring at Frances. Tom took offense when the bloke came over to the table and offered to buy the ladies wine. A bit of a scrimmage broke out and the patron, reportedly 6’4" and weighing 350 pounds, left with a broken nose. The story made front page of the Inter Ocean and page 2 of the Tribune, both with pictures of Frances -- you have to love the hats.

After a run of 3 month’s run at the Garrick the play went on tour the second week of January, 1911, Frances leaving it in April in Ottawa when she was 6 or 7 months pregnant with Frances junior. It was a year before Frances appeared in the newspapers after Frances was born on July 7, 1911: that was an appearance at a “monster memorial” show for a recently deceased popular sportswriter on July 21, 1912 and was followed by beginning rehearsals in New York for a show that would open on Broadway on November 13th, The Red Petticoat.

The Red Petticoat was Jerome Kern’s first complete score, (Footnote: Wikipedia article on this being Jerome Kern's first complete score is undocumented, but seems to be borne out by Kern’s obituary in the NY Times, November 12, 1945. Kern was best known for Show Boat. ) a Shubert production that starred Helen Lowell, with Frances in the role of “Sage Brush” Kate - another show with huge chorus of some 75 people. (Footnote: IBDB. ) After mixed reviews and two theaters on Broadway it went to Brooklyn and then on tour to Pittsburgh - Hartford - Boston - Chicago, and then Buffalo where the show ended April 6, 1913.

In the summer of 1913 Frances won a part in A Broadway Honeymoon at the Joe Howard Theater (formerly the Whitney). A musical comedy treating satirically the confusing divorce laws around the states it was to have had Sophie Tucker in the cast, but she withdrew over a dispute over prominence in the cast. (Footnote: Chicago Tribune, August 26, 1913, page 10. Online biographies of Sophie Tucker are devoid of information on her career in this time period, but a quick review of the papers in Illinois indicate that she appeared in a number of venues in and around Chicago from 1909 onward with regularity. Frances would appear on the same vaudeville billing as Sophie in 1918 at the Majestic in Chicago. ) The show, which opened October 3rd and closed in Bloomington November 27th was short lived despite a nice review in the New York Clipper which says Frances is “…loveable in a light comedy role. The show is neat, compact, busy, and a bully evening’s fun.” (Footnote: New York Clipper, October 11, 1913. ) It is likely Frances tried to squeeze in a benefit show when she took a leading role in a minstrel/vaudeville show with an all-women cast of 80, a first for the newly formed Northwestern Women’s Athletic Association. She is listed first in the cast on November 7th, but there is a different leading lady in the reviews of the two performance show on December 6th. (Footnote: “Choose Star Cast for W.A.A. Show,” Daily Northwestern (Evanston, Il), November 7, 1913, page 1, and succeeding reviews in the same paper, especially the one on December 9th which says that a new leading lady was hurried into the part. ) She likely left for rehearsals of September Morn, which opened December 20th at the La Salle.

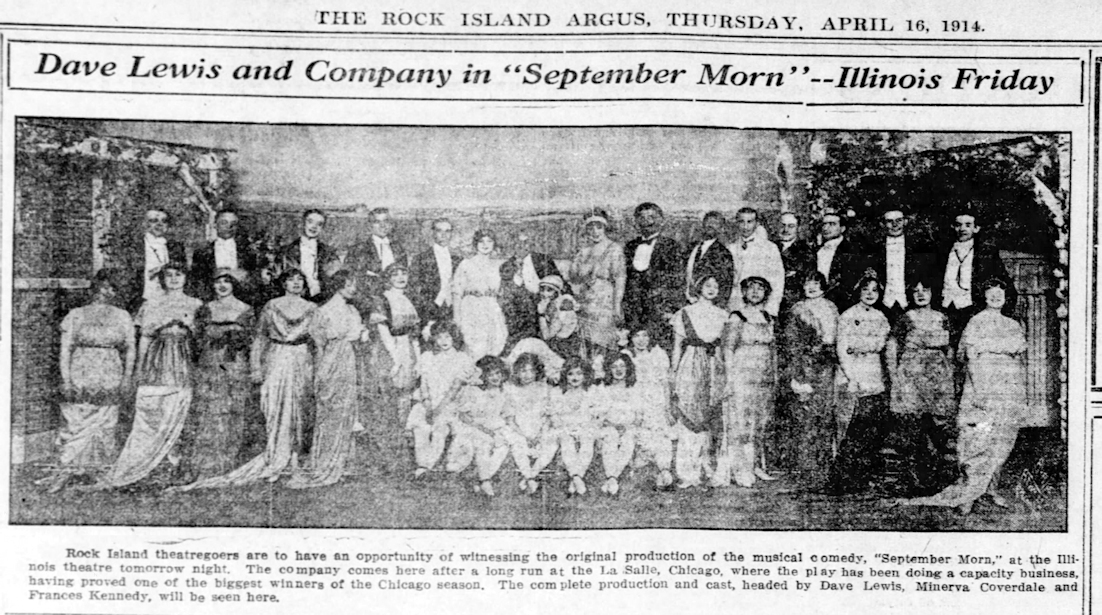

“Frances Kennedy, who has adorned more Chicago casts than any one player who could be named, is one of the decided ‘hits’ of the performance. She plays an arch, cooing widow, with an offspring whom she addresses as her ‘first and only son,’ and her comic flutter is delicious.” So reads the review of September Morn which otherwise did not think too much of the comedy, claiming it was an attempt to exploit the notoriety, in Chicago and around the world, of a painting by that name of a nude bather. (Footnote: Review: Collins, Charles W., Chicago Inter Ocean, December 22, 1913, page 6. For the controversy over the painting in Chicago see "The September Morn Hoax." There is also an extensive Wikipedia article on the painting, the controversy, and the films and music it inspired. People were arrested for displaying the painting, sending it through the mail, and a host of other offensive actions. It was a different age. )

In a mixed review in the Chicago Tribune Frances is given much credit for her rendition of the ballad “Beautiful Dreams I’m Dreaming.” Whatever the case, the evidently popular musical comedy ran from December 20th at the La Salle for 15 weeks until the first week of April, then dying in the Quad Cities in western Illiois and eastern Iowa at the end of April. In the reviews and notices Frances rose above, or at least equal to, the stars Dave Lewis and Minerva Coverdale.

On July 19, 1914 Frances joined the cast of The Elopers at the La Salle Opera house. After a 3 month run it closed in Alton, Illinois September 18th, and Frances headed back to New York and Broadway. She is listed in the cast as one of the many “guests” in The Lilac Domino which opened at the 44th Street Theater on October 28th, closing on Broadway January 20, 1915 after 109 performances. (Footnote: IBDB, “The Lilac Domino," IBDB, "The Lilac Domino" There is also a Wikipedia article on The Lilac Domino. There was a film adaptation released in 1937. ) Whether Frances stayed with the cast for the duration or perhaps took breaks from it is not known, but in a curious diversion from her usual, she appeared at Orchestra Hall on November 26th singing opera with Eusebio Concialdi, then a young baritone who sang and taught in Chicago for many years following. (Footnote: “Eusebio Concialdi,” Obituary, Chicago Tribune, October 30, 1965, page 32. Also many notices and ads in the Chicago papers over the years. The 1923 Handbook of American Private Schools lists “Eusebio Concialdi Music School, 410 S. Michigan Ave., Eusebio Concialdi, Director.” (Google Books) )

Seemingly after a break, Frances joined the cast of Within the Loop on August 29, 1915 when the huge musical revue had been in rehearsal

for 5 days. It opened in Buffalo November 22th with Frances as a headliner in a cast and chorus of 125 with anywhere between 38 and 34

musical numbers in it depending on which newspaper you look at. It was, as the Buffalo Courier wrote on the

24th, “…live-wire entertainment mixed with peppery songs and flavored by dashes of brilliant color…” Following Buffalo it

traveled to Detroit for a week, then Pittsburg for a week and finally in Chicago at the Chicago Theater on December 29th.

After several weeks it opened in St. Louis on January 23rd, then played in Indianapolis - Muncie, Indiana and Cincinnati, closing in

Dayton, Ohio the second week in February with everyone going home. The Washington Post wrote on the 20th that it was supposed to come there,

but had closed.

In the Dayton Daily News February 7, 1916:

“Frances Kennedy of ‘Within the Loop,’ boasts of being somewhat of a politician. Her husband was at one time county attorney in Chicago and in the last campaign there, she sang at the various meetings in behalf of the Democratic ticket. She is prominent in suffrage circles since in Illinois the women have a vote. She has two beautiful children at home, one nine years and another four and at the close of the season she intends to retire permanently from the stage and devote all her time to her household and political duties.” (Footnote: Dayton Daily News, February 6, 1916, page 11. )

Vaudeville

She may have been contemplating retirement, but actually she was to launch into a vaudeville career that would bring more recognition than her career in musical comedy. Two and a half years later and well into a career in vaudeville she told a Pittsburgh reporter, “Have you ever seen a fly trying to disengage himself from the entangling influence of a sheet of fly paper? Well, that is what I am doing. I am trying to retire from the stage.” (Footnote: “Singing Comedienne at Davis Next Week,” Pittsburg Press, September 22, 1918. With picture. ) It didn't happen; she was trapped like the fly by her love of the stage. While she spent the summer and fall of 1916 developing her act, by the end of the year she was booking with both the Keith’s and Orpheum circuits. Thirty-two year old William B. Freidlander, who would produce shows on Broadway in the 1920s and 30s, wrote a few songs for her and she took those, along with her quips and jokes, on the road to towns in which she already had some name recognition from her years in musical comedy. While she did a solo billing at the Wilson Avenue Theater (Footnote: The Wilson Avenue theater opened in 1909 with vaudeville shows. It still survives at 1050 W. Wilson in Chicago. For many years now it was a bank, but plans were afoot in December, 2018 to reopen it as a music venue; The Palace, in Fort Wayne, has been demolished but there are pictures online of what it looked like. ) in September, in December she was at the New Palace theater in Fort Wayne, where she was known and loved. Already billed as “The Merriest Comedienne” and recognized for her fabulous gowns, the reviewer in the Fort Wayne Daily News had an interesting take on her transition to vaudeville:

“As paradoxical as it may seem a musical comedy star almost invariably is a flat failure in vaudeville. Fort Wayne has seen dozens of former favorites of the light opera world essay vaudeville only to flivver miserably, which makes the riotous success of Frances Kennedy at the New Palace all the more noteworthy. Miss Kennedy was a musical comedy star of the first magnitude…and now she is repeating in vaudeville only more so.” (Footnote: “Repeats in Vaudeville,” Fort Wayne Daily News, Dec 19, 1916, page 4. )

Bloomington, Illinois - Ann Arbor, Jackson, Flint, Kalamazoo, Michigan in January of 1917; Moline, IL and Chicago in February and March in St. Louis led up to this review in Variety:

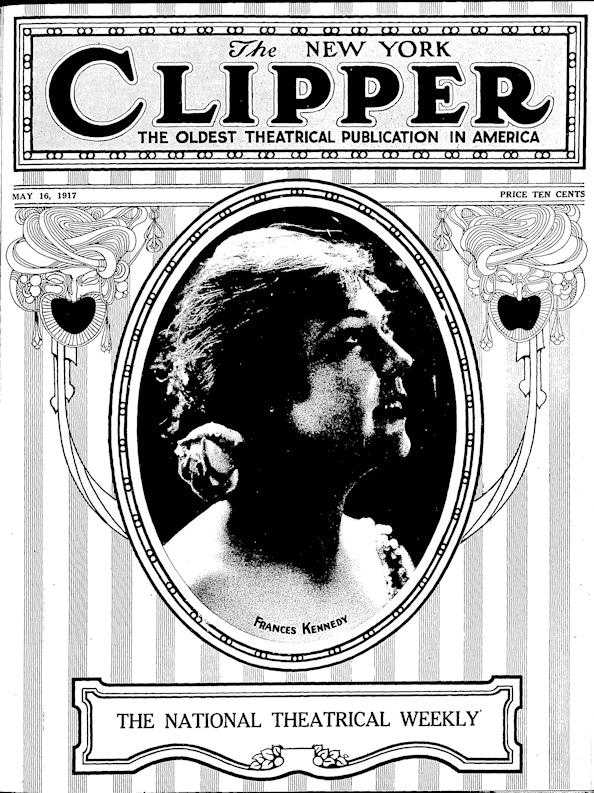

“Again a whale of a show was dished out to a capacity audience, and not only was there quality to the bill but quantity, with the opening act sent out at 8.07 and the finis being recorded at 11.15. Seldom is a show so productive of hits, but a majority of the nine acts won that honor Monday night. Unquestionably Palace audiences are demonstrative, yet this week the laurels were earned on merit. Frances Kennedy, from musical comedy, was fourth, and aside from the fact that she is a Chicago girl was showered with blooms enough to fill a young florist shop; she came very near stopping the show. Miss Kennedy flashes a wonderful smile, sends over her numbers in a natural, intimate way and knows how to wear pretty clothes.” (Footnote: Variety (New York, NY), March 23, 1917, page 40. )

Variety, and its competitor, the show-biz trade magazine The New York Clipper, (Footnote: The New York Clipper, founded in 1853 was absorbed by Variety in 1924 having run some 72 years. Variety came into being in 1905. ) were noticing Frances to the point where she appeared on the cover of the Clipper in May of 1917 with a recognition on page 5 that she is “…one of Chicago’s most talented singers. She possesses a clear, well trained voice of excellent quality which she uses with fine effect in the rendition of either classical or popular selections. She is equally at home on either the concert or vaudeville stage and has appeared on both with marked success.” (Footnote: New York Clipper, April 16, 1917, cover and page 5. )

An Aside on Vaudeville.

When Frances took to the vaudeville stage it was at the beginning of its decline, but had at least a decade and a half of life left in it. Silent films would sometimes be part of a billing but by the end of the 1920s, when the “talkies” came in, vaudeville lost out to that two-dimensional world of popular entertainment. It was under the firm control of two major billing agencies which controlled not only who performed, but many of the theaters they performed in: the Orpheum and the Keith circuits. Who performed was rigorously controlled by the Vaudeville Managers Association which discriminately gave thumbs up or thumbs down to acts based on how morally clean the act was. If you used off-color jokes or unacceptable words in your act you were given a thumbs down. Benjamin Franklin Keith and his wife Mary set the tone from their first theater, the Bijou in Boston, where he would putter around the theater fixing things while she dusted the chairs and cleaned upholstery. (Footnote: Gilbert, Douglas, American Vaudeville Its Life and Times, (1940), Whittlesey House (New York – McGraw Hill). Page 201. Gilbert’s book is also a great resource for the history of vaudeville, its performers and managers. ) For a performer, or his or her agent, the ultimate words to hear were “give him a route,” which meant from forty to eighty weeks straight time. (Footnote: Ibid, page 214. ) Frances would get routes in her career, but never that long. Needless to say, hers was a clean act, but satirical as we shall see.

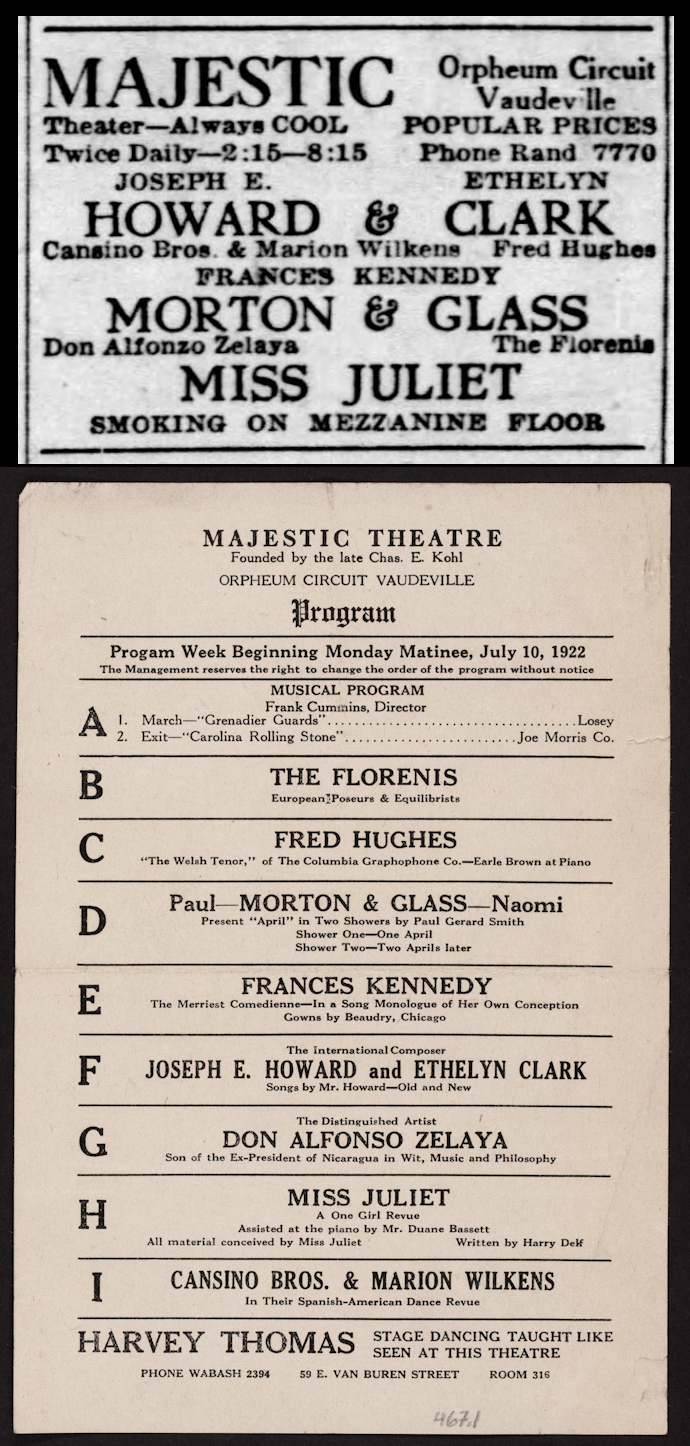

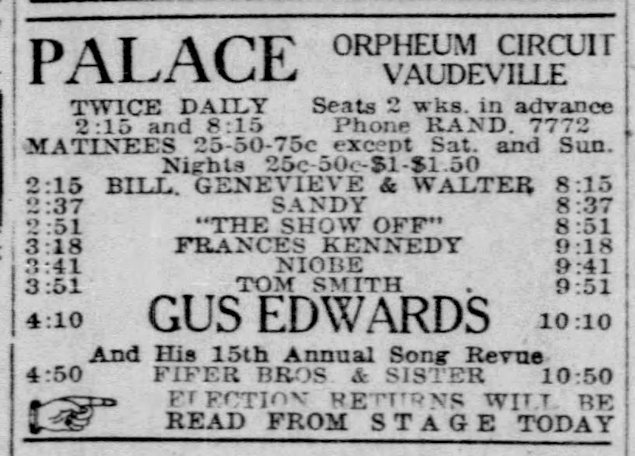

Vaudeville was not a variety show where a parade of performers come out quickly followed by another after a song or five minutes of jokes, like the Ed Sullivan show, Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour, or the reality star shows of today, which, of course, have a lot of filler between acts. Instead it was a show where anywhere between four and eight acts would do 20 to 30 minutes followed by another. Shows would go on sometimes four times a day starting at 11 a.m. and ending around 11 that night, but two shows a day was more typical. An act's placement in the show was worked out by the theater manager, not necessarily indicating "top billing," that occurred in the advertisements, usually with the size or placement as the ad and program for the same show at the Majestic shows. The ad for the November show at the palace shows the timing of the show that day. As one can see from that ad, Frances had 23 minutes allotted. These programs and ads are quite typical.

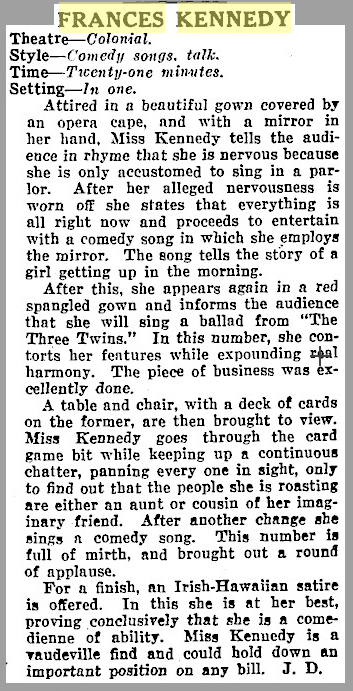

So what did her act look like?

The description of her show at the Colonial in January, 1918 tells it better than anything. As for the jokes, they appear to be of the Joan Rivers, Rodney Dangerfield, Phillis Diller brand of poking fun at men, women, and husbands. While it is difficult to know what songs she sang, the Chicago Tribune occasionally ran a column called "Why They Laugh in Vaudeville." The jokes Frances told are from that column in two issues in 1919. If they don't make you laugh just remember: you probably needed to be there; timing is everything.

"Why They Laugh at Vaudeville" - Frances Kennedy.

- “Oh, dearie, just look at Mrs. Gray. She’s so thin if there was draft she’d blow through the key-hole. Why she can use her elbow for a can opener, it’s so pointy.”

- “I should say my husband is not a hard drinker. The idea. Why, drinking is the easiest thing he does. Dry Sundays don’t bother him any. He comes him (sic) with such a load on Saturday nights that he is unconscious until Monday.”

- “Do you see Mrs. Brown over there? Hasn’t she a lovely back for a billboard? ‘No beer, no work,’ or something like that. And just look at her cheap silk stockings, they’re so thin I can read the serial number on her money. This idea of using your stocking for a bank is all right – that, the principle is all right – but it draws too much interest.” (Footnote: “Why They Laugh in Vaudeville,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 1919, page 64. )

"Why They Laugh at Vaudeville" - Frances Kennedy.

- “See that woman? She’s quite and athlete – always jumping at conclusions. See that dress she nearly has on? Well, as she shows so shall wee peep. She asked the clerk for something to match her complexion and he sent her to the leather goods department.”

- “This tea is so weak it must have strained itself when it went in the cup.”

- “That woman is so thin she could use her elbow as a can opener. She tore some of her eyebrows – that’s why she looks so surprised.”

- “Someone said her husband is a hard drinker, but I always thought it came pretty easy.”

- “My husband is a good provider. I have two kinds of meat at each meal – hot tongue and cold shoulder. He went to a store to buy some hose for me the other day. The saleslady said, ‘Do you want them for your wife or do you want more expensive ones?’” (Footnote: “Why They Laugh in Vaudeville,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1919, page 67 )

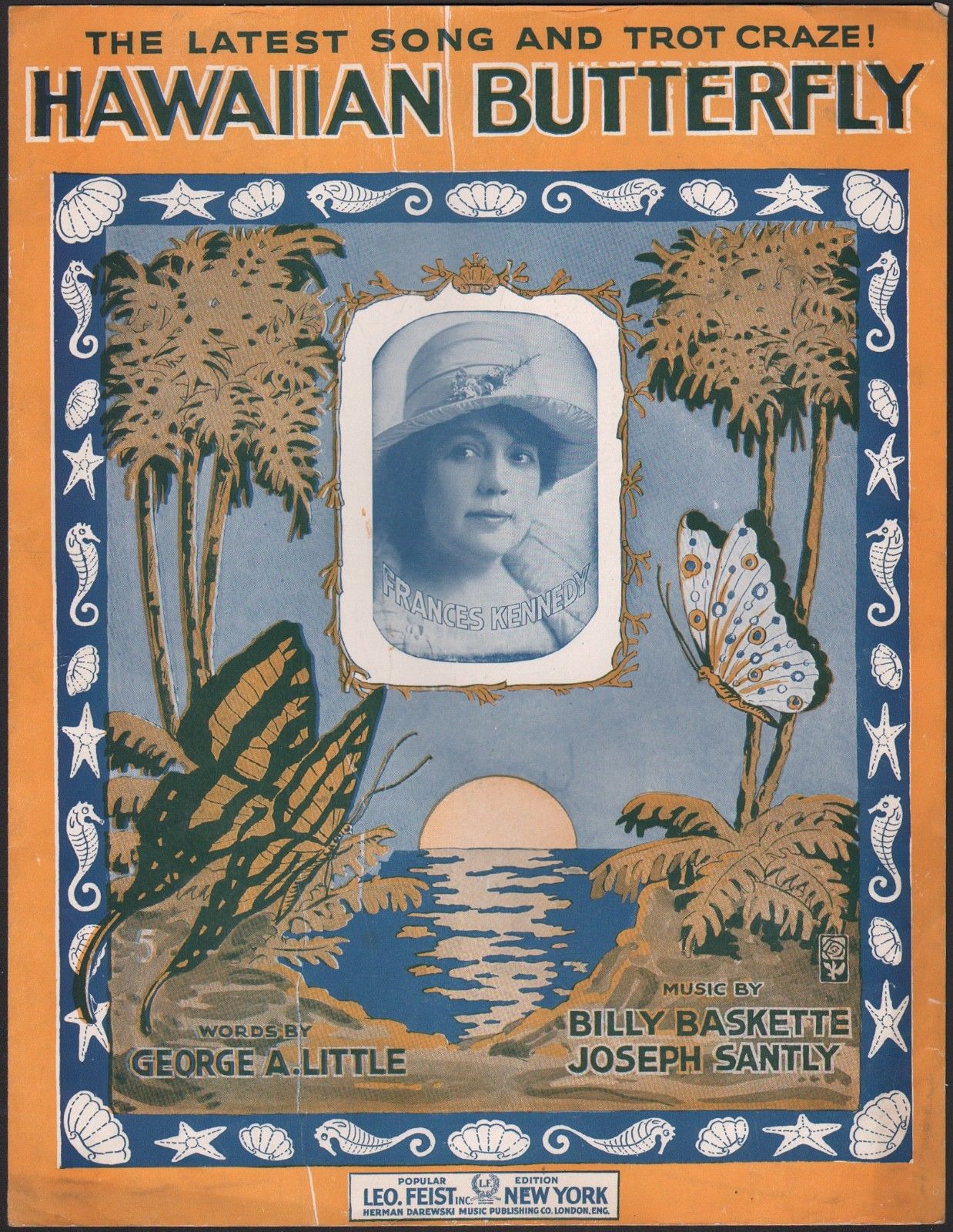

Reviewers never put the song titles of her songs in the reviews. It is assumed that she bought songs from a variety of songwriters besides the ones from William Friedlander that she started out with. Occasionally ads for her shows would have “Songs by so-and-so” below her name, but the only one that I’ve found is “Jean Haves,” who I know nothing about. Curiously, I’ve found two pieces of sheet music on E-Bay, one of which I bought, that feature her picture on the covers.

With only her picture on the cover there is no reference to her singing it, but then these songs were sung by a number of artists on the stage. “Let’s All Be Good Pals Together,” copyright 1919, was recorded by Ernie Erdman (1879-1946) in 1920 and we can pretty confidently assume that Frances sang it on stage. Erdman's recording is online at the University of California Library's Alexandria Digital Research Library. As far as I know Frances never recorded anything. She no doubt sang Hawaiian Butterfly as well, which is also online at the Alexandria Digital Research Library (This one is weird, no lyrics.) (Footnote: Both recordings accessed January 23, 2019. )

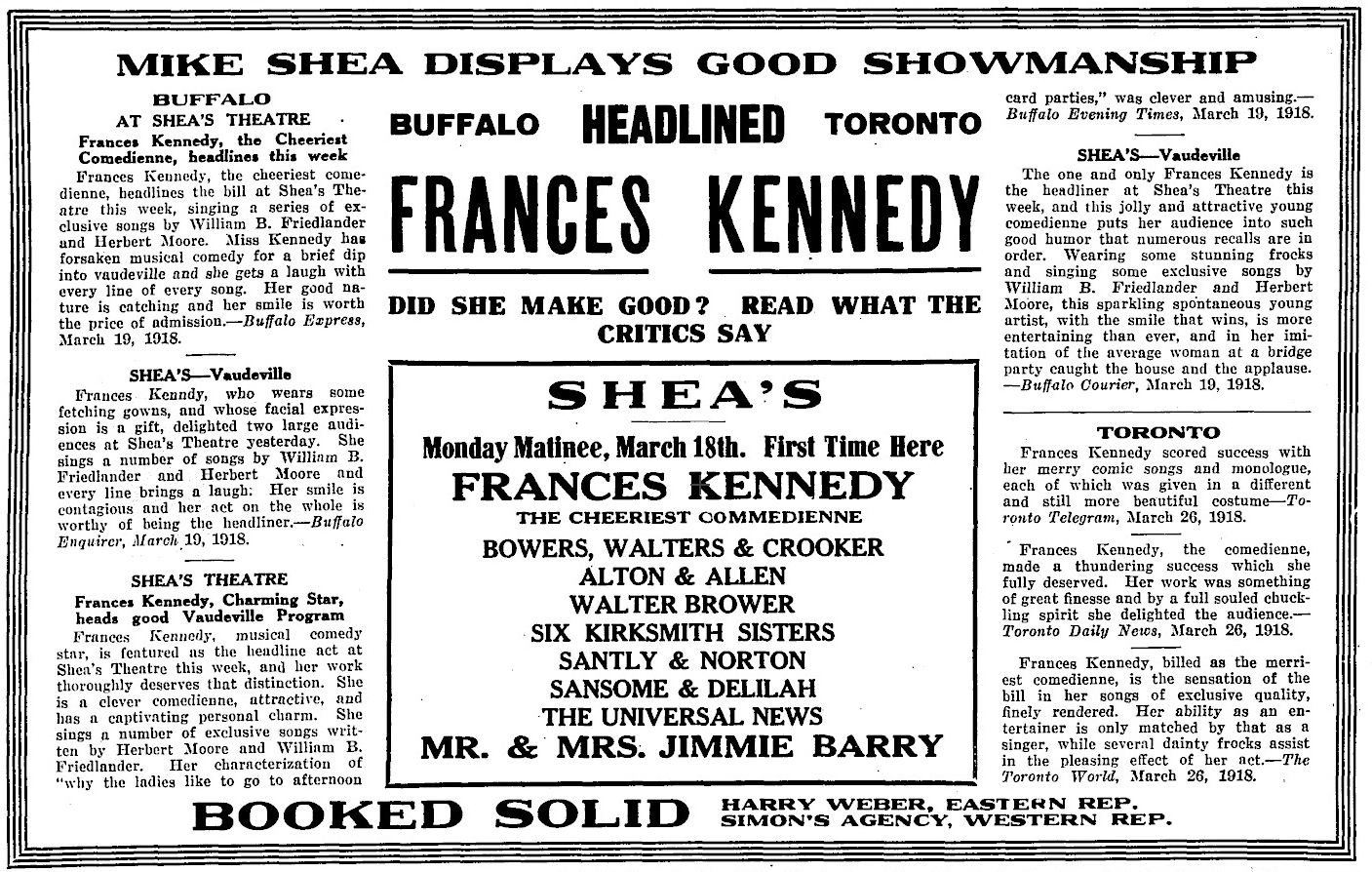

Frances was very familiar with Buffalo, and Buffalo with her. Her agents no doubt placed the ad for her at Mike Shea's in March of 1918 in The New York Clipper. Frances had performed in Buffalo in the musical comedies and as a vaudevillian she would return to Buffalo a number of times in the future.

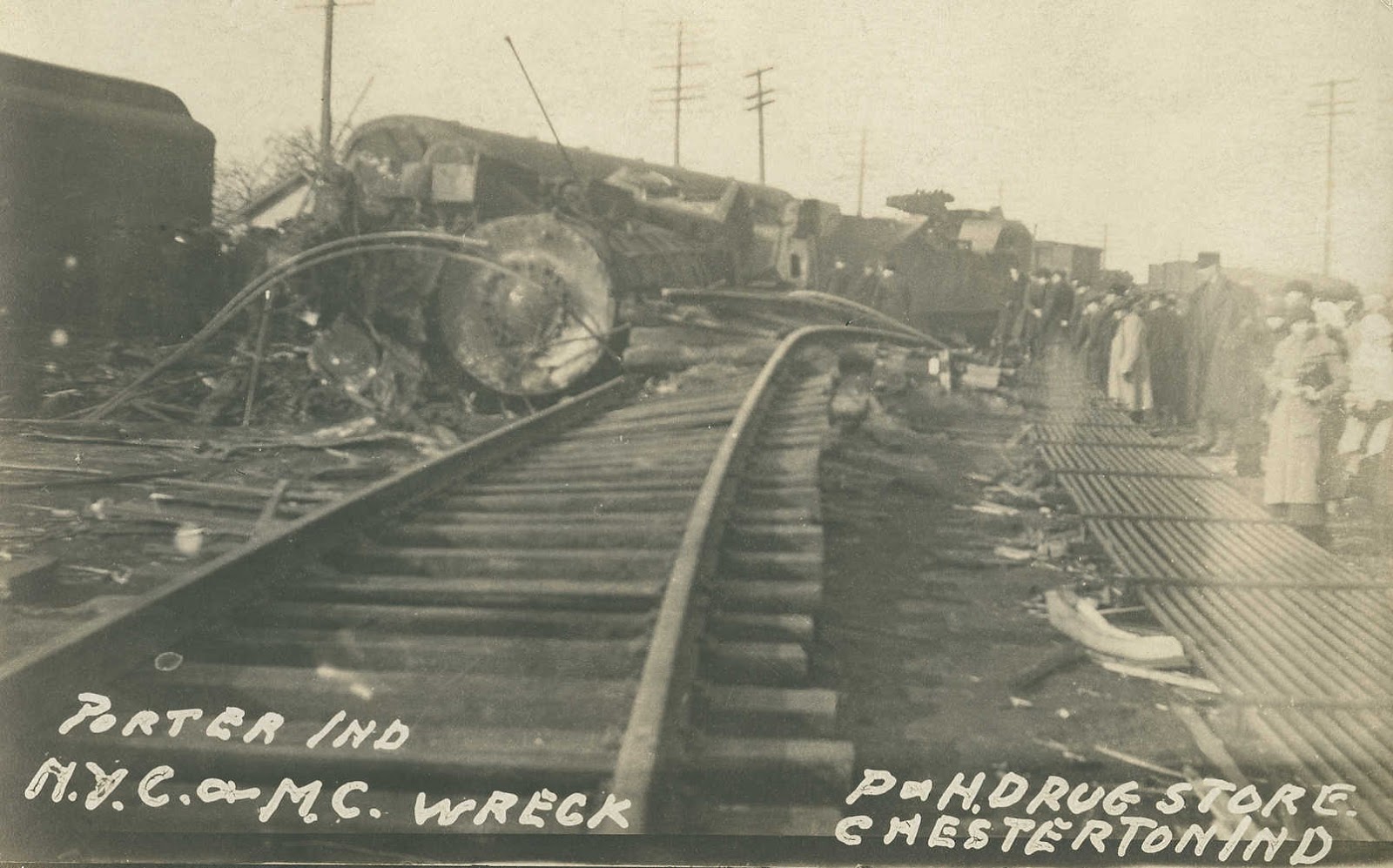

While 1918 through 1921 were busy and jam packed with billings and shows, I’m going to focus on only two seasons beginning in the fall of 1921 to the spring of 1923 to give sample of what vaudeville entailed for the performer. Two incidents stand out that are worth noting, one for her being heckled in late May, 1920, the other for her near death in a train accident in Porter, Indiana in February of 1921.

Heckled and Composed.

The heckling incident was reported on the front page of the New York Clipper’s June 1920 issue with the title “Rowdies Busy at Royal.” While I’ve not been able to pin down exactly what town or theater this was, or find other newspaper accounts, the incident seems to me to be anti-Irish inspired; I can’t think of any other reason.

“Rowdies got busy Monday night at B.F. Keith's Royal, during the performance of Frances Kennedy’s act. Miss Kennedy, a comedienne, was doing a character number,

seated at a small table, when someone in the first balcony started a volley of applause. This went by unnoticed, as did several other like rounds, Miss Kennedy

refusing to let the noise interfere. Then the person trying to raise trouble started banging something around, and the house lights went up. Miss Kennedy then

inquired of the audience whether or not there was trouble, or whether someone else wanted to say something. Someone then remarked “Take her off, Go ahead and leave."

Miss Kennedy left the stage, saying “All right, I thank you.”

Then the house went into an uproar. There were cries of “Miss Kennedy, come back and do your act, the audience wants you, don’t mind those rowdies,” and the like.

Miss Kennedy did come back and made a little speech in which she said : “I thought I would have to go to England, or France, or Europe to be treated like this,

I didn’t think that Americans would treat an American this way. I have done this act for four years in the principal theatres of the country, and never has this

happened to me, I am sorry that I had to come to the Royal to have it happen.”

These remarks were greeted with loud applause, until someone in the mezzanine boxes got up and yelled out, “Miss Kennedy, perhaps if you changed your name for this house you would be heard.”

To that she replied: “I am sorry, but I was born with the name of Kennedy, and if you folks want to hear my act, I will try and sing a number for you.”

More applause greeted this announcement and she sang a number, which was applauded for fully a minute. Then , taking several bows, she walked off. No act on the bill, which

completed its routine, received so much applause as Miss Kennedy then did; in fact she stopped the show for fully five minutes.”(Footnote:

“Rowdies Busy At Royal.” New York Clipper, June 2, 1920, page 1.

)

In the same issue the reviewer of the show wrote, "Frances Kennedy is entirely too clever a woman to have deserved the treatment she got from this audience, or, rather, a disagreeable part of it. Miss Kennedy's gameness was admired by the better part of the crowd and her rebuke for the treatment accorded her took effect, resulting in her scoring a personal triumph over and above artistic victory."(Footnote: Ibid, page 10. )

A Broken Nose.

It seems obvious that Frances would have spent a lot of time on trains. It’s likely that gigs within a couple of a hundred miles of Chicago were punctuated by training home to be with her family, longer tours not so much. At the end of February, 1921, after a series of performances in New York state, the last being in Binghamton, the New York Central train she was on collided with a Michigan Central train in Porter, Indiana - a terrible wreck that killed 37 individuals. The wreck, and her being in it, was widely reported around the east, the New York Evening World putting her picture on the front page with the story; some reports initially had her as one of the dead. She told the Chicago Tribune reporter that after being thrown to the floor and knocked out, she revived with only a broken nose and some bruises and walked up to the wrecked cars. The Hammond Times reported that she then aided in the care of the injured.(Footnote: Chicago Daily Tribune, Feb 28, 1921, page 3; Hammond Times, Feb 28, 1921, page 7. )

(For a detailed examination of the accident in Porter see Steve Shook's page on the wreck. where there are a lot more images as well.

1922-Two Seasons on the Road - Summer in Miller Beach

While she performed many places the rest of 1921, we pick up her travels beginning in January, 1922: billings in Minneapolis - La Crosse - Olathe, Kansas - Sioux City - Madison, Wisconsin

on the Orpheum circuit. Back in Chicago at the beginning of February she did a fill in at the Majestic and her 11 year old daughter turned theatrical, writing and producing a

playlet that was presented at the Chicago Summer School on February 3rd.(Footnote:

“Little Frances Kennedy Writes,” Variety, February 17, 1922, page 9. The play was called “Blossom Time in China.”

) On to Rockford the first week of February, St. Louis for the week of the 12th, two shows a day

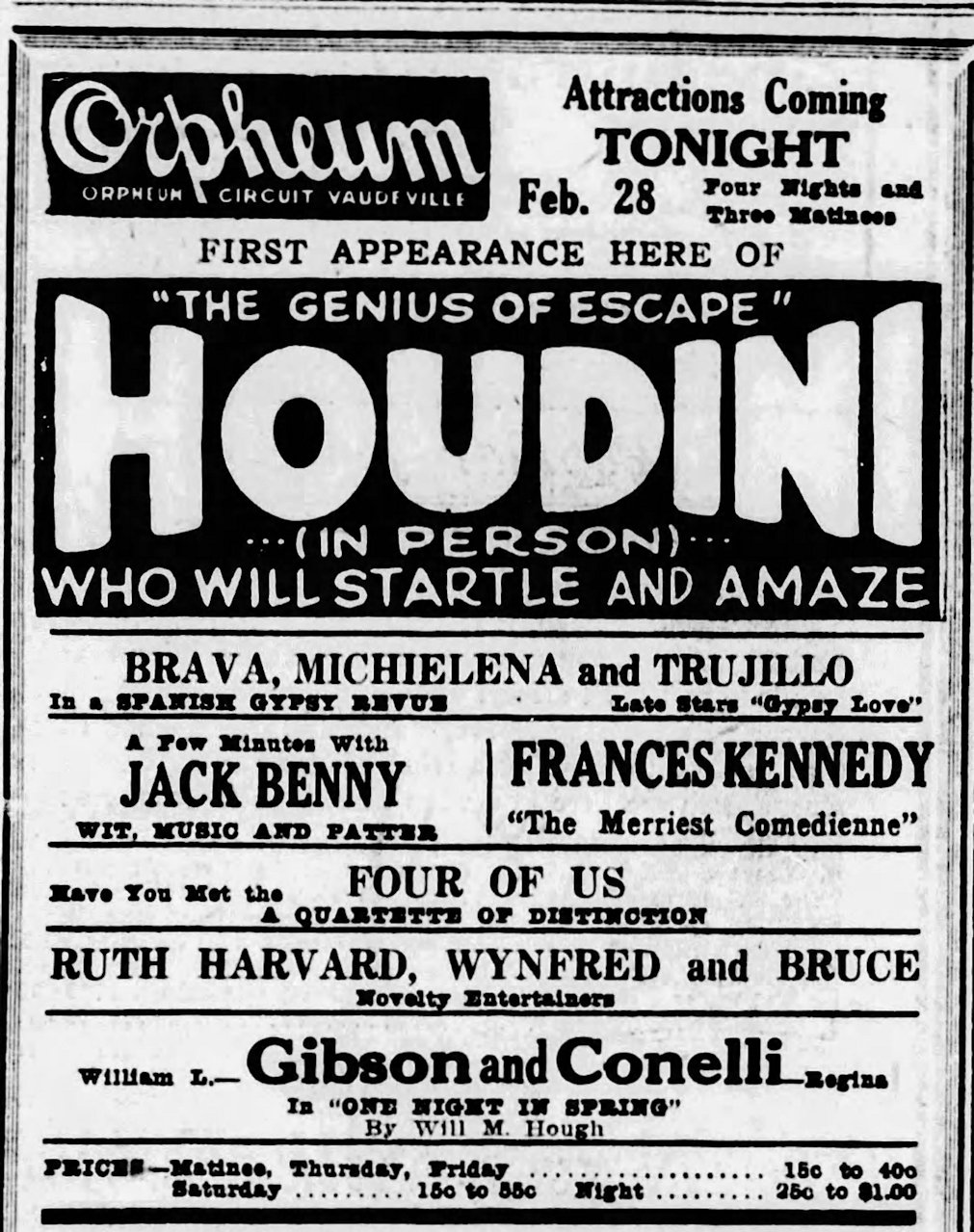

followed on the stage by Houdini. And then back to Rockford - Davenport and Madison until March 11, then to Springfield, Illinois, and Chicago. She’s an “added feature” in

Charlotte, North Carolina for a week in the middle of March. After her trial in Chicago on March 22, more about that below, she was in South Bend for a week

starting the 27th, on the same billing as the magician Horace Goldin, whose act was to saw a woman in half.

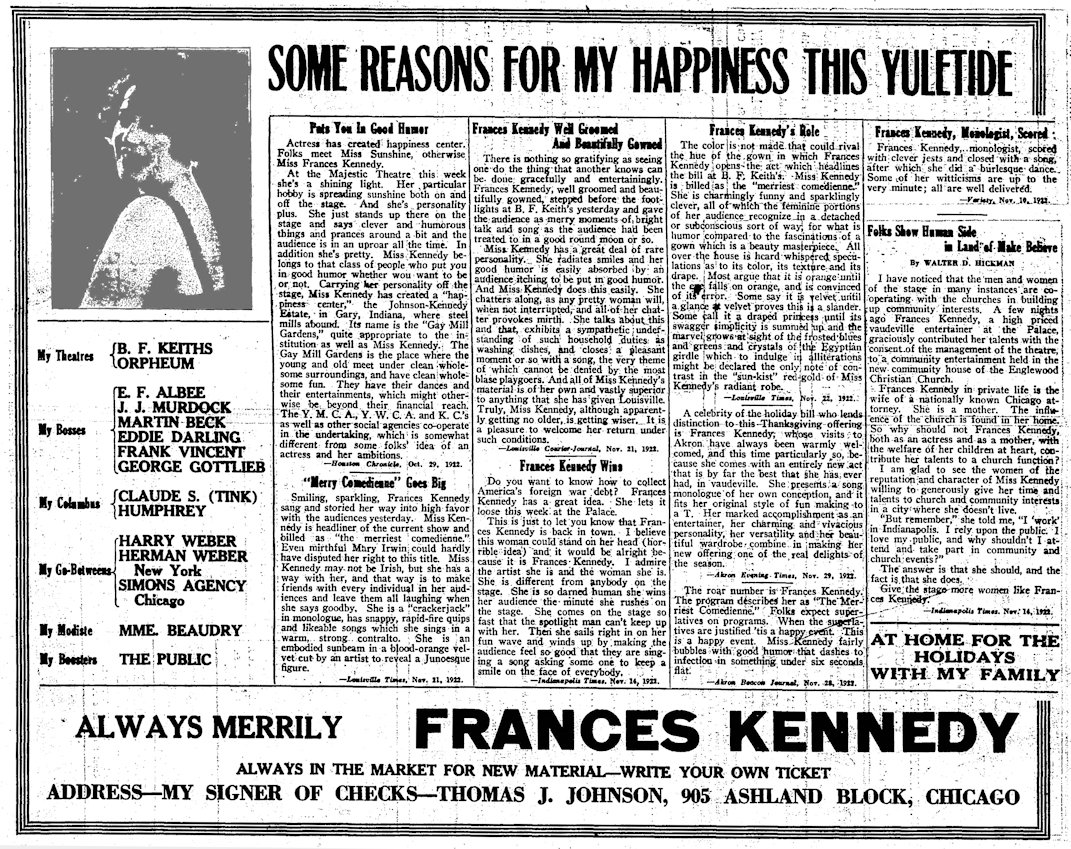

Fashion Plate Frances

In very many reviews, both long and short, of her shows it is mentioned how fabulous her gowns were and that she would have changes, sometimes as many as three, in her short 20-30 minute bits. Her favorite modiste, according to the ad in The New York Clipper, was "Mme. Beaudry" who was likely Florence Beaudry who was in business as a dressmaker in Chicago.(Footnote: Ancestry.com: City Directories of Chicago and the 1920 and 1930 censuses in which she is listed as a dress maker. Also her ads in Chicago papers in 1913 after which she doesn't appear to need any more business. ) Indeed, when Frances was in Cincinnati in October of 1923, the Cincinnati Enquirer ran her picture with the headline, “Known as Fashion Plate.”

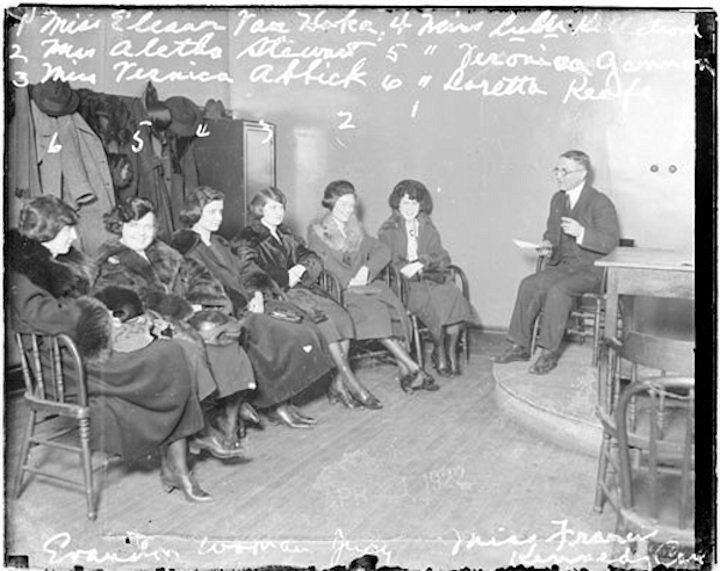

Likely she used a number of different dressmakers in Chicago, one unlucky one was Morris Kutock, an Evanston tailor. When he failed to have a $175.00 (about $2,600.00 in 2017 money) dress ready for pickup on February 4, 1922 Frances refused it after her tour of several cities to the west.(Footnote: Variety shows her booked in Sioux City, Iowa the week of January 30th as well as Rockford and Madison in the early part of February. ) Kutock took her to court and in a decision recounted around the country in many papers, lost his case in front of an all women jury, the first of its kind in Illinois; Frances claimed that in three weeks it had gone out of fashion. Theater historian Angela J. Latham discusses this case in her book Posing a Threat, pointing out that Frances’ win likely may have had a detrimental effect in the progress towards women taking part in the judicial system in Illinois, where they had just won the vote.(Footnote: Latham, Angela J. Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and Other Brazen Performers of the America's 1920s, 2000. Print. ) While, according to Latham, newspaper accounts portrayed Frances as coy and artful in her testimony, she definitely had the sympathy of the six young women on the jury. Latham claims that the socio-economic status of her husband and defense attorney no doubt helped her, but it should be remembered that Frances herself was well known among theater goers in Chicago, young and old.

For a transcription of the United News Service wire on the case the appendix.

Gay Mill was getting underway, and the April Variety made note on page one of her being a prize-fight promoter at Gay Mill. This was Tom’s doing though, for she was still very much involved in vaudeville, performing at the Kedsie in Chicago and then Racine for three days. She also got involved a musical comedy, “And Very Nice, Too,” that opened in Montreal, Canada May 8th at the His Majesty’s Theater.(Footnote: “New Musical Play Has Its Premiere,” The Gazette, Montreal, Canada, May 9, 1922, page 9. ) According to the Montreal papers, the play had rehearsals in New York and theater managers were in Montreal to preview the play for possible openings in New York, but evidently the show fell by the wayside when one of the actors was jailed for bigamy, convicted and sentenced to two years in the Kingston Penitentiary. (Footnote: The Gazette, May 8, 1922, page 6; June 3, 1922, page 1. ) The play ran for two weeks and died there in Canada.

Frances was in Boston for a show June 8th, then Detroit before returning to Chicago where she was at the Majestic in July. In August and September it was to the south: Houston - San Antonio - Wichita - Little Rock - Oklahoma City - Tulsa, and New Orleans on the Orpheum circuit, ending in mid-October with a return in early November to Chicago’s Palace theater, reviewed in the New York Clipper, “Frances Kennedy, being a Chicago favorite, received a warm reception and incidentally some roses at the close of the act. Frances has the happy faculty for making ones troubles fade into oblivion via her clever monologue and personality. The patrons kept her working until she begged off with a speech of thanks.”(Footnote: “Palace (Chicago),” New York Clipper, November 8, 1922, page 10. )

The week of November 11th she was in Indianapolis and then went on to Louisville - Akron - Cincinnati and Dayton before returning to Chicago with a December 27th billing at the

State-Lake which was reviewed in the Clipper: “Frances Kennedy, who is really “The Merriest Comedian,” in every sense of the billing ,

gives distinction to the show. Her clever way of telling stories, and rendering songs, makes you forget every worry you ever had.

Her adorable personality simply radiates through the audience until everyone wants to rush up on the stage and hug her. Miss Kennedy is one artist who is always welcome on any bill,

and of whom one can never tire.”(Footnote:

“State-Lake (Chicago),” New York Clipper, December 27, 1922, page 10.)

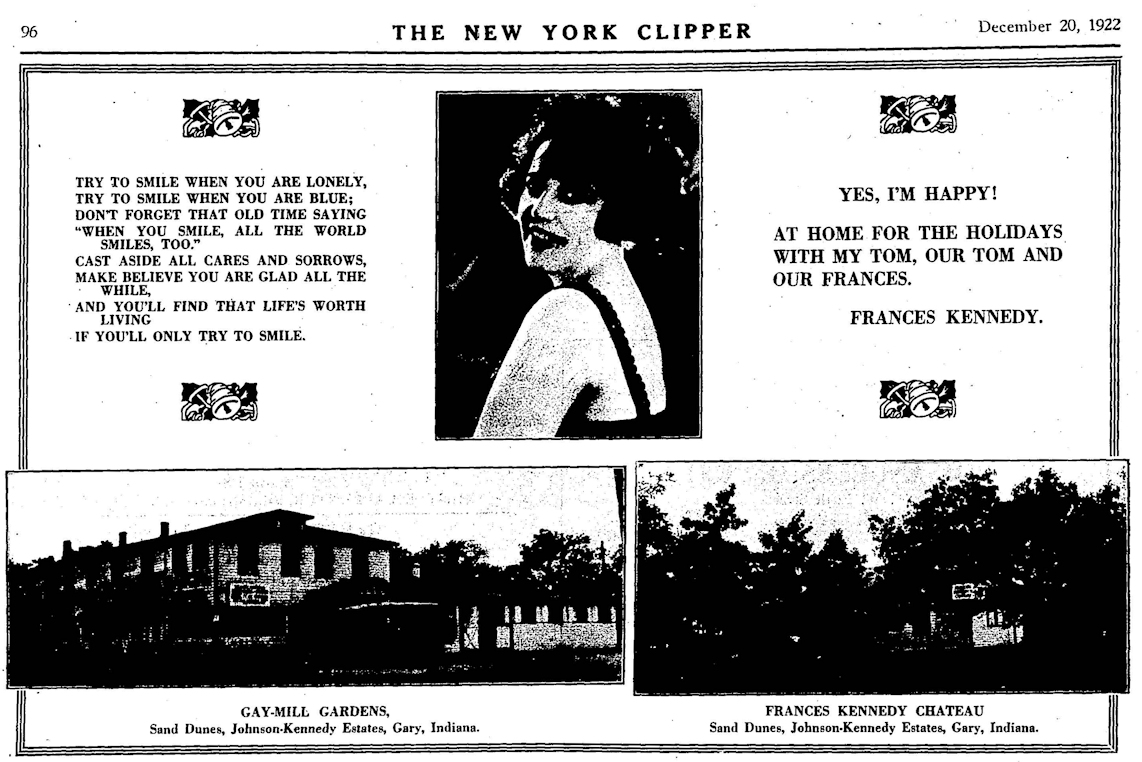

In December she took out a full page ad in The Clipper and Variety exclaiming her happiness to be home, and thanking all her supporters. Note the last line: "Address - My Signer of Checks..."(Footnote: “Some Reasons For My Happiness this Yuletide,” New York Clipper, December 13, 1922, page 33; Variety, December 15, 1922, page 29. ) That was followed a week later in the Clipper with a “Christmas Card” that featured pictures of herself, Gay-Mill Gardens, and her “Chateau” in the sand dunes of the Johnson-Kennedy Estates.(Footnote: New York Clipper, December 20, 1922. (Unfortunately the only originals of the Clipper are at the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library. Clippings that I’ve downloaded are from microfilm digitized at the Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Photos are never clear in microfilm.) )

Into 1923: Canada and California with Jack Benny and Harry Houdini

After a last week in January performance in Richmond, Indiana on the Orpheum circuit she hooked up on billings with 29 year old Waukegan native Jack Benny and 49 year old Harry Houdini for an Orpheum tour starting in Winnipeg that would go to Vancouver, British Columbia, and then on to San Francisco. (Footnote: Billings are from Variety. ) In San Francisco Jack and Frances were reviewed in the same paragraph: “Jack Beeny (sic) plays well on the violin, at the same time keeping his audience in a continual state of laughter. “The Merriest Comedienne” is Frances Kennedy who, with a song monologue of her own conception, brings individuality in the role of a songstress.” (Footnote: San Francisco Examiner, March 17, 1923, page 20. Billing ad is in the same paper on March 20, page 11. )

After the San Francisco shows, Frances changed billings to the Oakland Orpheum theater where the Oakland Tribune gave her a headline review titled “Frances Kennedy Wins Orpheum Headline Place – Dainty Comedienne Romps Off With Laugh Honors in Well Balanced Bill.” After two shows in San Bernardino, ads reading “You’ve Seen Eva Tanguay – You’ve Seen Trixie Friganza – Now see Frances Kennedy, Variety’s Brightest Star”, she went on to Los Angeles to hook up with Houdini again in shows at the Hillstreet Theater for a week.(Footnote: Oakland Tribune, April 3, 1923, page 31; Advertisement, San Bernardino County Sun, April 15, 1923 page 16; Advertisement, Los Angeles Times, April 23, 1923, page 21. ) The tour ended there and Frances took the long train ride back to Chicago and Miller Beach for the summer, but not before she sent a telegram to the New York Clipper from Los Angeles to tell them she was finishing up her Orpheum tour and to wish The Clipper a happy seventieth anniversary.(Footnote: New York Clipper, May 9, 1923, page 33. ) Perhaps if she’d have stayed in Los Angeles she would have become famous like her co-worker that spring, Jack Benny.

Gay Mill Garden Days

Having spent the summer of 1923 in Miller Beach, the following years until 1931 followed a pattern of winter vaudeville tours, first in the east then more Midwestern in 1926

and following years. In 1924 she got recognition in a number of papers around the country as being a philanthropist with Gay Mill by providing a play place for steel workers.

In 1929 the Cincinnati Enquirer ran an article on how she had come up with the “revolutionary idea” of setting up a children’s nursery at Gay Mill. (Footnote:

“Model Dance Hall Has For Feature A Child Nursery,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 20, 1929.

) This had been going on for some time, for the Baltimore Sun mentions the nursery in an article about her in 1925.(Footnote:

“She’s ‘Angel For Gary Steel Mill Workers,” Baltimore Sun, March 22, 1925.

)

In the summer months she directed Gay Mill and broadcast from radio station, WJKS, “Where Joy Kills Sorrow,” which she and her husband had launched in 1927 and operated from Gay Mill.(Footnote:

You can learn more about WJKS at the Gay Mill page on this website.

)

When she left on her 1927-1928 winter tour the Hammond Times ran a note that “Radio fans heard the voice of Miss Frances Kennedy for the last time in several months from Station WJKS,

one of the owners last night when the program dedicated in her honor, as she bids a temporary farewell, leaving today on her annual winter vaudeville tour."(Footnote:

Hammond Times, September 28, 1927, page 15. (Transcribed exactly as it appears.)

)

When she performed at the Lyric in Indianapolis in 1930 the Indianapolis Star captioned her picture with “…a radio star…dubbed by her listeners as ‘The Voice of the Steel City.’”

By 1931 Gay Mill had run its course as a dance hall; in the spring of 1931 Frances reportedly sold the radio station to Atlass Investment company, the ex-WBBM owners.(Footnote:

Hammond Times, April 4, 1931, page 5. She and Tom may have sold a portion of the station, but it continued to broadcast from 540 N. Lake Street until 1933. See for more information on WJKS.

)

In 1929 the Cincinnati Enquirer ran an article on how she had come up with the “revolutionary idea” of setting up a children’s nursery at Gay Mill. (Footnote:

“Model Dance Hall Has For Feature A Child Nursery,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 20, 1929.

) This had been going on for some time, for the Baltimore Sun mentions the nursery in an article about her in 1925.(Footnote:

“She’s ‘Angel For Gary Steel Mill Workers,” Baltimore Sun, March 22, 1925.

)

In the summer months she directed Gay Mill and broadcast from radio station, WJKS, “Where Joy Kills Sorrow,” which she and her husband had launched in 1927 and operated from Gay Mill.(Footnote:

You can learn more about WJKS at the Gay Mill page on this website.

)

When she left on her 1927-1928 winter tour the Hammond Times ran a note that “Radio fans heard the voice of Miss Frances Kennedy for the last time in several months from Station WJKS,

one of the owners last night when the program dedicated in her honor, as she bids a temporary farewell, leaving today on her annual winter vaudeville tour."(Footnote:

Hammond Times, September 28, 1927, page 15. (Transcribed exactly as it appears.)

)

When she performed at the Lyric in Indianapolis in 1930 the Indianapolis Star captioned her picture with “…a radio star…dubbed by her listeners as ‘The Voice of the Steel City.’”

By 1931 Gay Mill had run its course as a dance hall; in the spring of 1931 Frances reportedly sold the radio station to Atlass Investment company, the ex-WBBM owners.(Footnote:

Hammond Times, April 4, 1931, page 5. She and Tom may have sold a portion of the station, but it continued to broadcast from 540 N. Lake Street until 1933. See for more information on WJKS.

)

Frances continued to tour in the fall of 1931, sometimes billed as “The Voice of the Steel City,” but appearances were getting fewer. In 1932, when she was on stage in Richmond, Indiana, the ad billed her as “The Marie Dressler of Vaudeville.” Two years later she was in Dayton, Ohio at the Colonial when the reviewer wrote, “Frances Kennedy, who as seen the best years of her youth captures her audience with a vengeance through her facial antics and light comedy, but somehow seems a bit misnamed as “The Marie Dressler of Vaudeville.” (Footnote: The Dayton (OH) Herald, November 10, 1934, page 6. Marie Dressler, who had been performing on state and screen, died that year at the age of 65. See her Wikipedia article for more on Marie. )

What about Tom?

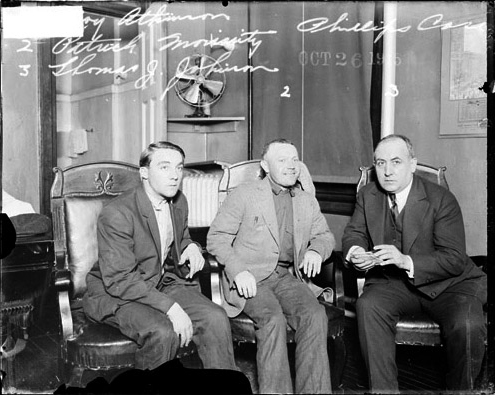

Tom (on the right) with Patrick Moriarity and Roy Atkinson, who were charged in the murder of Harry Phillips, a West Madison street jeweler in October of 1915.

Thomas J. Johnson had been wooing Frances for some time before she finally realized that she was in love with him and agreed to marrying him at the end of the run of The Isle of Bong Bong. Newspaper stage reporters are always looking for “behind the scenes” stories, and one dug this out in a 1908 column called “Good Wives in Chorus.” (Footnote: “Good Wives in Chorus,” Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1908, page 73. ) Most of what is known about Tom, as she referred to him in the papers, was written by Archibald McKinlay in 1989 in the Hammond Times.(Footnote: McKinlay, Archibald, “Calumet Region winds down to radio station.” Hammond Times, April 9, 1989, page 76 Main Edition. ) Tom was the prosecuting attorney for the City of Chicago sleuthing out and prosecuting arsonists when they married.(Footnote: In one such case he prosecuted a 17 year old arsonist for setting at least 16 fires. “Confess to More Fires,” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1904. ) McKinlay wrote that in the wake of the deadly Iroquois theater fire of December 30, 1903 that it was Fire Inspector Johnson who cracked down on theaters around the city enforcing and creating codes for theaters. Leaving public service Tom became a very successful criminal defense attorney, getting acquittals in 84 murder cases according to McKinlay.

He evidently made a good deal of money, between them a two income family. Frances maintained in a 1926 “stage door” interview that “Some of our greatest actresses are beautiful examples of wives and mothers, and a great number of them are still on the stage…”(Footnote: “Stage Women As Wives,” Indianapolis Star, March 28, 1926. ) Frances no doubt included herself in that number. In an article in the Baltimore Sun in 1925 she talked to the reporter about her marriage and how they discussed both his cases and her act: “’When I can make him laugh,’ says Miss Kennedy, ‘I know I’m good. Then I know I can make the world laugh.’”(Footnote: Baltimore Sun, 1925, op. cit. )

In 1923 he was named chief arbiter of the Showmen’s League which had been formed in Chicago in 1913 with Buffalo Bill Cody as its first president. “With powers similar to those enjoyed by former Judge Landis in baseball,” his task was to “clean up” all outdoor amusements, carnivals, circuses and fairs throughout the United States.(Footnote: “Outdoor Showmen Pick Commissioner to Purify Business,” Chicago Tribune, March 19, 1923, page 21. ) While this was likely needed, not everyone appreciated the high-handedness, one columnist calling Tom the “High Exalted Ruler, Supreme Kleagle, and Omnipotent Overlord…Grand Boss of the circus, sideshow, carnival, and amusement world. The Judge Landis of the circus is given unlimited powers and may impose a $10,000 fine and three-month suspension on any African lion that talks back to him.”(Footnote: Phillips, H. I., “Overlording the Outdoor Show World,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March, 26, 1923, page 15. This an amusing rant. ) The impetus to “clean up” the fairs and circuses came from the publication of “Confessions of a Fair Faker” in Country Gentleman Magazine in June of 1922.(Footnote: The Country Gentleman, (Philadelphia, PA), Volume 87, April 8, 1922, page 4 ff. Online at The HathiTrust. ) Despite the grumpy, but funny Philadelphia editorial, many papers around the country applauded the new efforts.(Footnote: An example is “It’s Now or Never For Carnivals,” Deadwood Telegram, Deadwood, SD, June 23, 1923, pp. 2-3. A rather long interview with Tom and his association with the Showmen’s League and his newly appointed position as Commissioner. ) Tom’s official title was general counsel and commissioner of the Showmen’s Legislative Committee of America. He continued to defend clients in Chicago as well.

Tom outlived Frances by nine years, dying in 1958. Their son, Thomas junior, had received his law degree from the University of Notre Dame and in 1935 achieved some notoriety defending the deportation of Anna Sage, the “Woman in Red” who had tipped off the FBI to John Dillinger’s whereabouts leading to his being killed in front of the Biograph theater in Chicago.(Footnote: “Attorney for Dillinger ‘Woman in Red,’” Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1991. Obituary. ) Daughter Frances had a successful career in retailing after graduating from the University of Michigan and after a brief period of following in her mother's footsteps in radio and theater.(Footnote: Obituary, Chicago Tribune, September 12, 1996, page 182. Other Editions. ) A monument to them is erected in Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois. (Footnote: A memorial to Tom at Find-a-Grave with a link to Frances' memorial and a picture of the monument to the family. )

The Dress Case Appendix

When Is a Dress Out of Style?

**********

Gown Can Be Utterly Passe in Month, First Woman's Jury Decides, Flouting Angry Male DressmakerAlexander F. Jones, United News Staff Correspondent, Chicago, March 22.

Jurors may have their troubles when it comes to the consideration of ethics of murder, but in taking up the more vital question of how long present fashions last, they are sure-fire, unanimous and instantaneous.

The first panel of women ever called to a jury box in Illinois proved this in Judge Witkower’s court in Evanston in one minute Tuesday by deciding that a gown created Feb. 5 may be utterly obsolete March 16.

Morris Kutock, foremost designer of women’s gowns on Chicago’s glittering north shore, appeared before the jury with one of his masterly creations on his arm.

Designer Wept.

Honest tears stood in his eyes as he described the grace of its lines, the inspiration of its creation, the incomparable softness of its fabric and the sheer genius in its blended colors.

His attorney backed him up and insisted that Frances Kennedy, the actress, pay $175 for it. Miss Kennedy had ordered it and simply refused to take it, he said.

The jury of her sisters looked inquiringly at Miss Kennedy. Her chances of winning the suit looked black indeed. She took the stand and in ten minutes Mr. Kutock went from there, sadly, the gown still under his arm.

Out of Style Now.

“It was like this,” testified Miss Kennedy. “I ordered the gown in January and it was to be ready positively by Feb. 4. Feb. 5 I had to go out on tour without the gown because it wasn’t ready.

“You see it is black charmeuse with flame colored georgette sleeves. It was lovely style when I ordered it, but, heaven’s sake, I couldn’t take it now. It is out of style. This man is silly to think I would.”

Miss Veronica Gannon, one of the jurors, leaned forward. “My dear, what were you going to wear with it?” she asked.

“Black silk stockings and satin pumps to match,” replied Miss Kennedy.

“Stunning,” interjected Mrs. Aletha Stewart, another juror. “It would suit your style beautifully.”

Everybody's Wearing It.

Judge Witkower rapped loudly for less conversation between the jury box and the witness stand.

“It would then,” replied Miss Kennedy, ignoring the warning, “but you girls know that everybody is wearing black charmeuse and flame colored now. It’s out.”

“Yes, everybody is wearing it,” said Miss Virginia Lawder, from the jury box. “But tell me did it fit?”

“I had to leave before I had a fitting,” replied Miss Kennedy.

“Without a fitting?” chorused the jury.

“If the ladies please,” the court commenced.

“Your honor, we find for the defendant,” said Miss Gannon, forewoman.

“Very well,” said Judge Witkower. And try as attachés might throughout the rest of the day, they could not find him.

Dress Case Jury

Story printed in the Des Moines Tribune March 22. Some form of it was printed in papers around

the country.

Photo above in the Chicago Tribune March 19th.

Jury photo: see photo credits below.

About this page.

This page grew out of researching the history of Gay Mill Gardens in Miller Beach, Gary, Indiana. I got interested in the people who had built Gay Mill, who were only named as vaudevillian Frances Kennedy and Attorney Thomas Johnson in existing histories. They had, however, brought the first radio station to Northwest Indiana not to mention a number of years of dancing and entertainment to the people of Gary, Miller Beach and the surrounding countryside.

In just an initial search on “Frances Kennedy” in Newspapers.com I got tons of hits for the years between 1904 to 1936 from all over the country. Intrigued, I began narrowing it down and slowly compiled a history of her career. I have a lot of things not included in this page, and there is likely more to be found. The study became more about theater, about which I know little, as it did about local history. To that end it provides a glimpse of what the life of a dedicated performer who was also a wife and mother might have looked like in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Frances never made a recording that I know of. She never went into films, which is likely one of the reasons she was never recognized by students of the era. She wasn’t flamboyant or outrageous like Eva Tanguay or some of the other vaudevillians, but she shared billings with, or “rubbed elbows,” with such as Sophie Tucker,(Footnote: Sophie Tucker worked a number of vaudevillian houses in and around Chicago in the first three decades of the twentieth century per the newspaper ads that appear. ) Jack Benny, and many of the stars of vaudeville in New York and the east; she shared a stage with Sarah Bernhardt at Chicago’s Majestic in 1918.

What I’ve learned about her career is mostly from the newspapers as well as the pages of The New York Clipper and Variety. There are a few pictures in the online digital collections of the Chicago Public Library and the Chicago History Museum but likely more in their archives, including playbills and programs. Feel free to contact me if you have any questions.

Page created January, 2019

© Text copyright: Steve Spicer

Feel free to contact me about this page.

A few resources used in this page.

- Newspapers.com was the primary source. Searching there is an acquired art but can be very rewarding.

- The New York Clipper 1853 to when absorbed by Variety is searchable at the Illinois Digital Newspaper Collection

- Variety is online at Archive.org but going there directly presents some cataloging problems. I found it best to go to The Media History Digital Library Hollywood Studio System Collection and scroll to Variety which will open a listing of the volumes by month. If you "Read" it will take you to archive.org's digitization which is then browsable or searchable.

- The University of Chicago has a huge collection of Playbills and Programs.

- The Chicago History Museum also has a huge collection of photos, playbills and programs. Listings of them by theater are A to H. and I to Z.

- Mentioned in the footnotes is Douglas Gilbert’s 1940 book American Vaudeville is full of stories and insights into the early history of vaudeville.

- John Kendrick's Cyber Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre, Film & Television is jam packed with information.

Photo credits not including those from newspaper captures:

- The Anna Held and cast photo is a composite made from image at the Jewish Women's Archive Encylcopedia crediting the Library of Congress and the cast photo from the Seattle History website. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/Held-Anna and http://www.seattletheaterhistory.org/photograph-record/scene-mamselle-napoleon respectively. Accessed January, 2019.

- Jolly Baron program from the Chicago Public Library's digital collection: http://digital.chipublib.org/digital/collection/CPB01/id/9372

- Yankee Regent cover is from the Sheet Music Warehouse: https://www.sheetmusicwarehouse.co.uk/20th-century-songs/

- A Knight for a Day program also from the Chicago Public Library's digital collection: http://digital.chipublib.org/digital/collection/CPB01/id/4928/rec/3

- Jumping Jupiter is from Wikimedia Commons

- Red Petticoat Boston performance herald is from a sales site, WorthPoint.com: https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/1912-jerome-kern-red-petticoat-musical-comedy

- September Morn is from WikiMedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oh,_You_September_Morn_title_sheet.jpg

- 1922 Majestic Theatre program is also from the Chciago Public Library digital collection: http://digital.chipublib.org/digital/collection/CPB01/id/3288/rec/2

- Sheet music covers are from eBay sales pages. "Let's All Be Good Pals Together" I purchased and the picture at the top of the page is a crop from that cover.

- Photo of Tom with Moriarity and Atkinson are from the Chicago History Museum searching "Archie". Original is from the Chicago Daily News photo archive online at the CHM.

- Photo of the dress case jury is also from the Chicago History Museum. DN-0074193, Chicago Daily News negatives collection. Informal portrait of (left to right) Miss Eleanor Van Hoka, Miss A. Stewart, Miss Veronica Abbick, Miss Lulu K., Miss Veronica Gemmon, and Miss Loretta Keafe sitting in a row with an unidentified man in front of them in a room in Chicago, Illinois. "Evanston woman's Jury Miss Frances Kennedy."