Dynamite: The Aetna Story

Aetna, the neighborhood of Gary that sits just south of U.S. 20 as one heads east from Interstate 65 has a history

that not many know about, a history that preceded it's being annexed by the City of Gary in 1927.

It was for almost four decades approximately 400 acres of nitroglycerin mixing sheds, factory buildings, dormitories, and office headquarters of the Aetna Powder Company making dynamite, smokeless powder, and gun cotton.

Additional Pages:

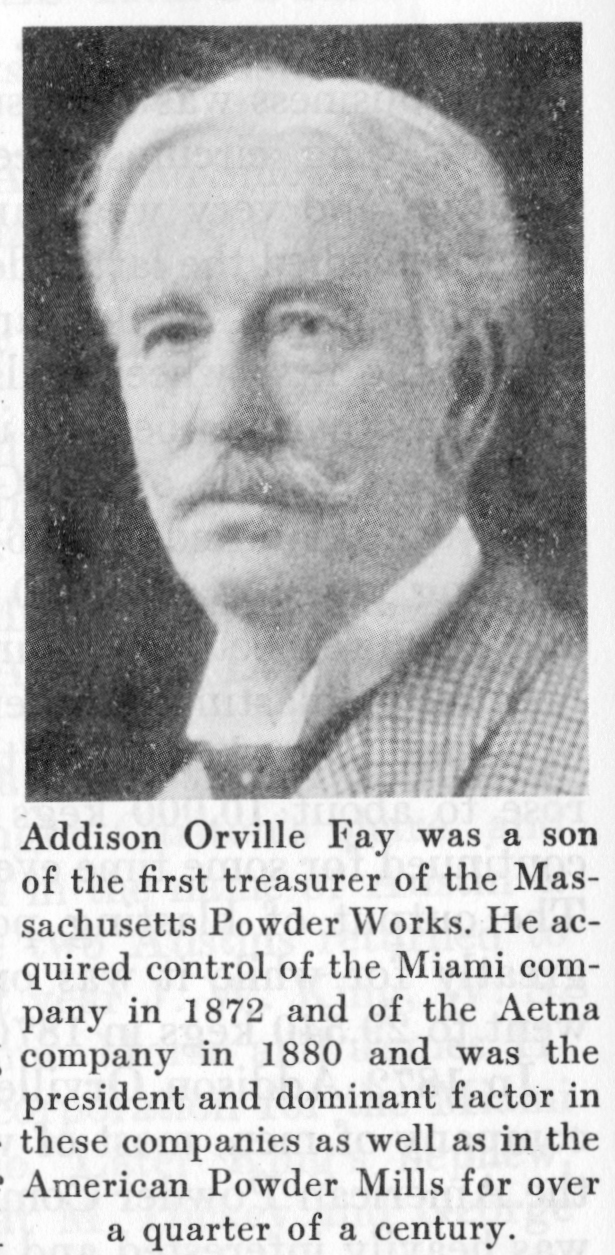

On April 3, 1880, three men from Chicago incorporated the Aetna Powder Company in Indiana to make high explosive powder, the newly invented dynamite. James Parker and Horace Pratt, coal salesmen, and Michael Tierney, a politician had little idea of how to build or run a dynamite factory. Their initial attempts to build on a spot near Schererville came to naught and Parker wisely turned to his old friend Addison O. Fay, president and owner of the Miami Powder Company in Xenia, Ohio. Fay was an old hand at the business of making powder, having owned mills in Massachusetts with his father, and having bought out Joseph King’s Miami Powder Company in 1877, enlarging it and operating it with electricity, the first mill in the country to do so. Dynamite was used not only in mining, quarry blasting, but also in tree stump removal as American farmers continued to clear land.

Fay got right to work in Aetna; fourteen months after Fay began building the plant in Aetna, Weston Goodspeed, wrote in Counties of Porter and Lake, Indiana (1882) that

“The works of the Aetna Powder Company are situated one and a quarter miles west of Miller’s Station, on the south side of the railroad. The surroundings are attractive, and the company seem to have found a favored spot in this desert region. Although this is called a “powder works,” no common powder is made here. It is all “high explosive powder,” and nitroglycerine is the active agent in the compound. Here it is manufactured in large quantities and absorbed into substances for shipment and use. It is only fourteen months since the company began here; now they have twenty-six buildings, employ forty-five men, and have a capacity of 60,000 pounds of powder a day. They are at present building another work (sic) and twenty workman’s cottages. When the new building is completed, the capacity will be 100,000 pounds a day. They now have in one building 185,000 pounds of high explosive powder in one storeroom, and 60,000 pounds in another. They own 200 acres of land are buying more. There are little hills and the small buildings are scattered among them, so as to have a sand bank between each two in which the deadly substance is handled. These buildings are connected by walks that wind about among the trees and hills, affording a much needed protection in case of an explosion.” (pp 541-542)

Explosions there were however… deadly explosions. The first one I’ve been able to discover was in 1888. Although one source mentions an explosion two years previous, I’ve not found newspaper evidence of that one. It does seem strange, and unlikely, that no explosions occurred for the first 6 or 7 years of the plant’s existence. There were twelve deadly explosions between 1888 and 1912, described on another web page.

A Successful Business

The company did a booming business in dynamite in the three decades leading up to World War One. The Chicago Drainage Canal alone took a million pounds.

It was used in the coal mines and stone quarries of Indiana which were replacing the use of black powder with dynamite. Shipments were at times made to

distant points, from Canada to Florida, and from Pennsylvania to Colorado, and even to Mexico and other foreign points. By 1901 the output reached 20,000 pounds a day.

The peak was about 1911 or 1912 when 2,000,000 pounds were produced in the record month and about 18,000,000 for the year. Until the early nineties mixing, packing, and

cartridge making were all done by hand.

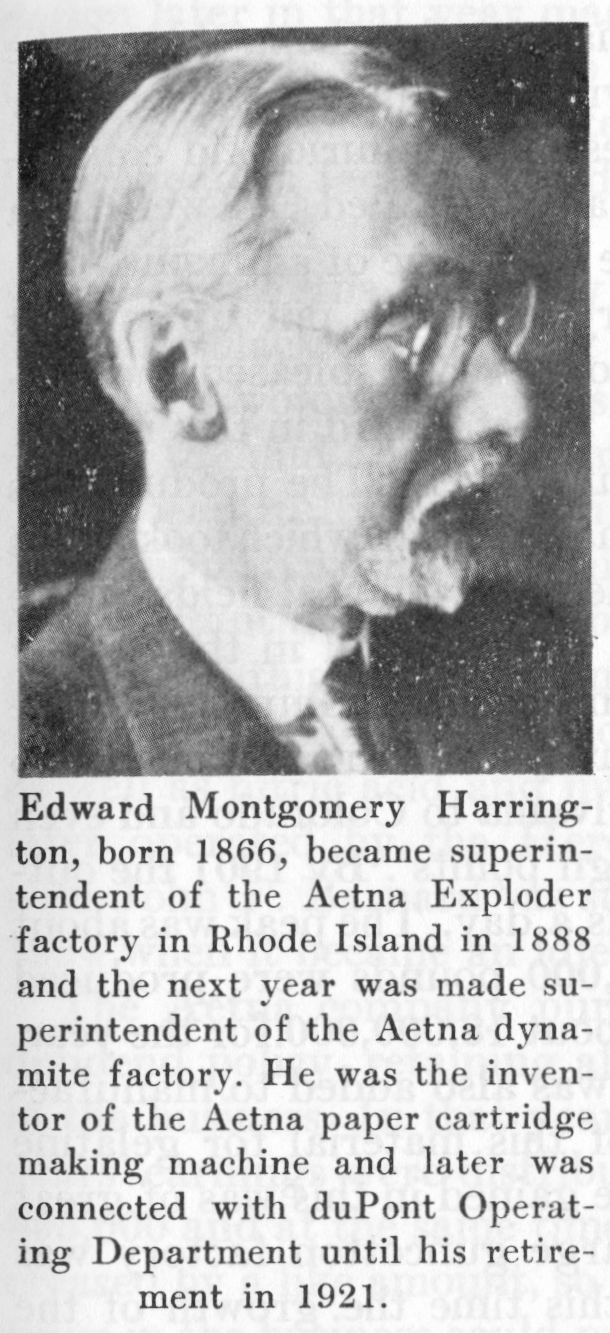

During the years preceding 1914 the principal offices were in Chicago with F.W. Penfield [1] the sales manager. There were important sales branches in Birmingham (Alabama), Duluth (Minnesota), Iron Mountain (Michigan), Louisville (Kentucky), St. Louis (Missouri), and Columbus, Ohio. James W.W. Smith, who had a close call in the explosion of 1888, was the first plant superintendent. He was replaced in 1889 by Edward M. Harrington who had been superintendent of blasting cap factory in Rhode Island that had been bought by A.O. Fay. Fay brought the blasting cap factory to Xenia as well as making Harrington the Aetna superintendent. Walter Wallace Edwards replaced Harrington in 1904, remaining as superintendent until the manufacture of dynamite was abandoned in favor of military gun cotton for World War One.

Transition

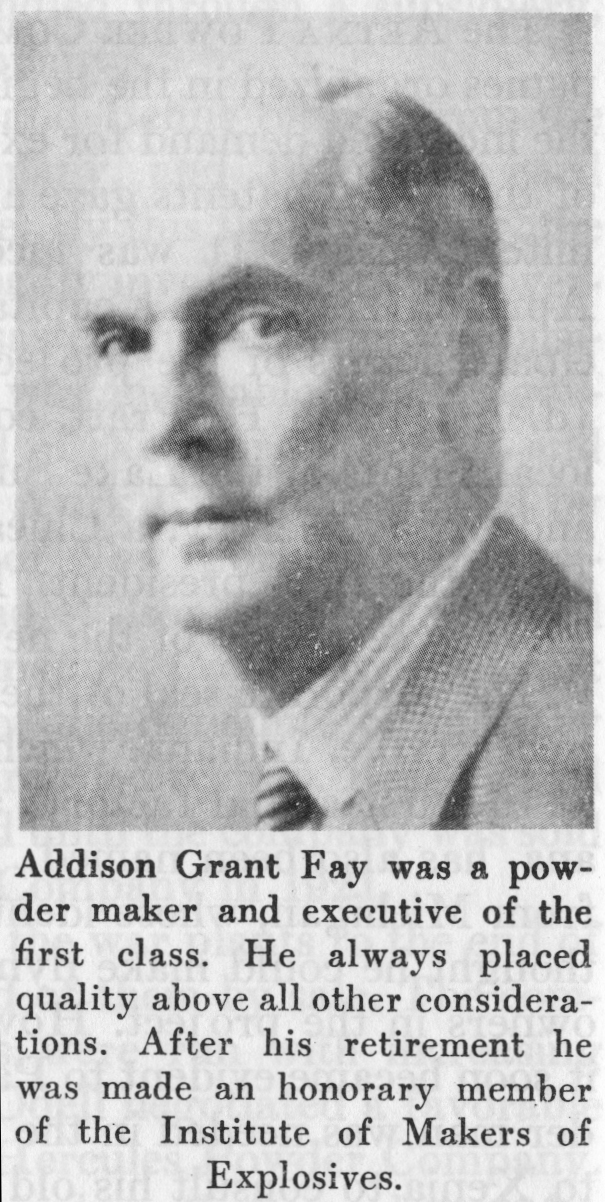

In the years following the deadly explosion of 1912 which killed six men the control of the plant was evidently slipping from the control of the Fay family. Addison O. Fay had died in 1906, his son Ralph two years prior to that [2], and the ownership of the company was in the hands of the younger son, Addison Grant Fay. The younger Fay was evidently not up to the job; in March of 1913 , subpoenaed in a law suit involving a Peoria powder company and the DuPont company Fay “…appeared before the examiner with his hands practically empty. He explained he had not been able to get together the documents and correspondence he was expected to bring.” [3]

While the production numbers appear to be substantial, it should be remembered that The Aetna Powder Company was actually a small fry in an industry dominated by the E.I. du Pont company. There were many companies manufacturing dynamite and competition was fierce, so fierce that in 1872 the major players formed a syndicate which came to be known as the Powder Trust, a price-fixing trust that was not broken up until 1912. Addison Fay’s Miami Powder company had been one of the original members of the Gunpowder Trade Association of the United States. The government claimed, in its 1909 suit, that the three companies, the Aetna Powder Company, The Miami Powder Company, and the American Powder Mills of Boston produced from year to year about 10 percent of the total output of all the powder factories of the United States. In November of 1914, an ex-director of the du Pont company, A.J. Moxham realized his plan to consolidate into one company the principal competitors of the du Pont by incorporating the Aetna Explosives Company in New York. The headline in The Times on January 7, 1915 read “AETNA POWDER CO. GOES OUT OF EXISTENCE.” Walter Edwards, the 38 year old superintendent of the plant and an Aetna resident, left to New York to supervise all of the Aetna Explosives Company’s plants and William Clayton took over as the local superintendent.

The War and Gun cotton

In 1915 the production of the plant took off. The Times reported on April 19th that a ten million dollar munitions contract was awarded and that the erection of a half-block long gun cotton factory was to be built that will require 800 operatives was beginning. The company also signed a contract with the Gary Heat, Light and Water Company to lay a 12 inch water main to Aetna which would provide two million gallons of water a day. On August 10th the Chicago Tribune reported that effective August first employees would receive a 10% wage increase which would be duplicated every month so that by June of 1916 operatives would be making 100% of what they were earning. The same article stated that the company had forty million dollars worth of war orders. The Times reported on September 4th in an article entitled “Explosives Big Boom,” that the plant was producing 45,000 pounds of gun cotton a day, there were 1,000 men at work, profits to be eleven million dollars. [4] They were shipping to the Bridgeport (Conn.) Projectile Company which was a German company evidently making shells for both the American government and the Germans, something that would stop once America entered the war in April of 1917. Another recipient of Aetna smokeless powder was the Canadian Car & Foundry Company’s huge plant in Kingsland, New Jersey which assembled shells bound for Russia and Britain. That plant was destroyed completely with a fire and explosions on January 11, 1917.

In October and November of 1915 another factory was built in Aetna by a subsidiary company, the Aetna Chemical Company, to manufacture Nysol, made from naphthalene and naptha, which is added to explosives to keep them from freezing. Spirits were high; The Times wrote on October 16th “That Aetna will continue to manufacture gun cotton long after the war to take care of America’s needs as outlined under the program of preparedness published in Washington dispatches today, is now assured.” [5] The years until the end of the war were prosperous for employees at Aetna; in February of 1916 The Times had reported that Aetna men were the highest paid in the county. Things were good for workers; there was a 10 percent increase in wages in May of 1918 and the building of an additional dormitory to house 80 more men even as the company advertised for workers.

Decline and the End

In the front office things were not so peachy. Like many companies that grow too fast and overextend themselves, Aetna Explosives was in financial trouble in 1917. Receivers were appointed in April of 1917; the company’s capital was exhausted. On top of that explosions and fires in plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania caused serious losses for the subsidiary company, Allied Chemical of Maine.

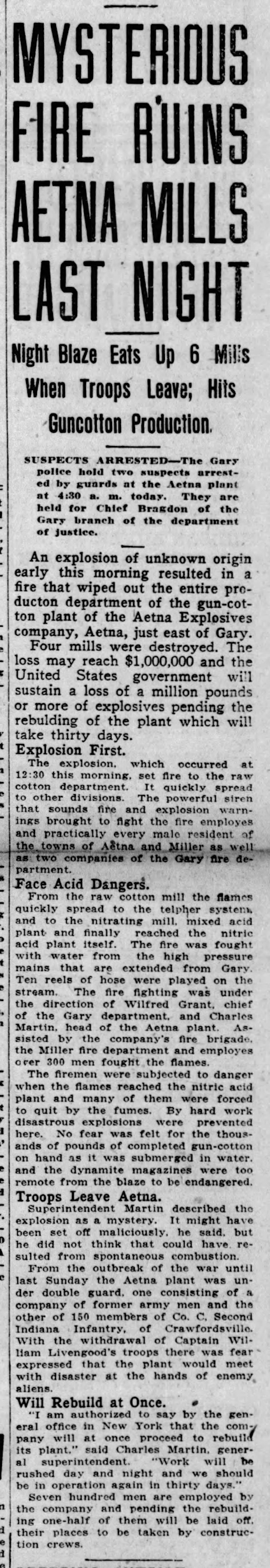

Story in the Times August 11,1917

In Aetna an explosion in August caused a fire that wiped out the entire production department of gun cotton, four mills destroyed which would take a month to rebuild. No one was killed however. The war went on; even a two week shut-down in the winter because of a crippling blizzard, or financial difficulties of the parent company didn’t stop production. It would all come to a screeching halt with the armistice of November 11, 1918. The orders from France were cancelled and Washington issued orders to ease up on production. The Times reported in February ot 1919 that the plant has practically shut down and in April, with a headline “Aetna is Losing its Identity,” announced that the plant was being dismantled and the town was down to five families.

On January 1, 1919 Bankers Trust Company of New York became trustee of the company and the finances of the company were reorganized. Aetna Explosives tried to hang on, publishing a 156 page book/catalog describing its products and how to use them in 1920. The cover of that book listed thirteen branch offices, nine large plants, and one-hundred and ten distributing stations, but it was all for naught, for in 1921 Aetna Explosives was sold to the Hercules Powder Company, one of the companies formed after the breakup of the Powder Trust.

In Aetna there was, very briefly, an attempt to use the site and buildings for a steel company. Chester E. Wirt, a Gary businessman, purchased as president of the Aetna Iron and Steel Company the old site to make, or fabricate, steel, but it never made it off the drawing board as financial difficulties put the company into receivership. Wirt not only failed on his mortgage but also his marriage, his wife winning a substantial divorce settlement in 1921, claiming her husband had another family in Syracuse, New York. The land of the old site was bought by residential developers in 1926 and Aetna was annexed by the City of Gary in 1927.

[1] Frederick W. Penfield (1873-1930) would go on to be mayor of Glencoe, Illinois and a member of the Chicago regional planning board. His relationship to the well-known fin de siècle artist Edward Penfield who drew the “Aetna Dynamite” poster is unknown.

[2] Find-a-Grave memorial with his wife and son Ralph

[3] The Times, March 22, 1913, page 7. A.O.Fay retired to New York City and then Winter Haven, Florida in 1924 where he established a winter home on a large estate on Lake Otis. He became a director of the Florence Citrus Growers association, dying in 1929 survived by his wife, a daughter and a son, and his sister, Mrs. H. C. Wright of Plymouth, Massachusetts. Find-a-Grave Memorial.

[4] One of those workers was Siegel Herbert Lee, the

grandfather of Miller business man Pat Lee. Pat still has his grandfather's medallion.

[5] October 16, 1915, page one. As one can imagine, the Preparedness movement in America, which began with the beginning of the war in Europe, saw tremendous opposition and controversy. President Wilson was initially opposed to it, but after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania passenger ship and the loss of 128 Americans in May of 1915, Wilson, along with others, began to see the writing on the wall.

Superintendents of the Aetna Plant

- One of the principal investors, M.J. Tierney seems to have been the manager and superintendent of the Schererville plant in 1880.

- James W. Smith was the first superintendent of the Aetna plant from 1881 to about 1889.

- Edward Montgomery Harrington (1889-1904)

- Walter Wallace Edwards (1904-1915) – an 1893 graduate of Cornell University in Mechanical Engineering.

- William Clayton became superintendent for one year when Walter Edwards left to become general superintendent of all of Aetna Explosives plants in January of 1915.

- Charles Martin. Head of the plant from 1916 to the end.

Pages relating to the Aetna Powder/Explosives Company

Comments and questions? Email Steve Spicer at steve@spicerweb.org