About 1994 I began trying to document the story of the Revolutionary War career of my GGG Grandfather, John Mott, which had been written by his granddaughter,

Amanda T. Jones, and subsequently perpetuated by my Great Aunt and her brother, my Grandfather. I was immediate put into a quandary when I discovered that

there were two distinct family lines that claimed the same man. I wrote a webpage in the late 1990s that reflected the confusion over two men named John Mott,

both Captains from New Jersey; that confusion was even recognized in David Hackett Fischer’s Pulitzer prize winning book on the Battle of Trenton, Washington’s Crossing.

Amanda T. Jones wrote her account of her grandfather in the introduction to her 1906 book, Poems, 1854-1906 and then reproduced it in her 1910 autobiography. Kate Mott wrote about her

grandfather in New York Genealogical and Biographical Record in April of 1894.

The parallels reflecting the confusion are remarkable and reproduced in an appendix web page.

The research had taken me to the David Library of the American Revolution at Washington’s Crossing, Pennsylvania, but it wasn’t for years that a blog post, Paucity of Militia Records Leads to Identity Crisis,

in that library’s newsletter provided me further understanding when Larry Kidder wrote

"The lack of official records relating to the New Jersey militia can cause identity problems. Since many men served at different times in both the Continental forces and the militia, it is difficult to know what the actual service of any one individual was. Was the man said to have been in the militia also the

same man who served for a time in the Continentals? Even standard and highly regarded sources can lead one astray. Here is one case study – Captain John Mott."

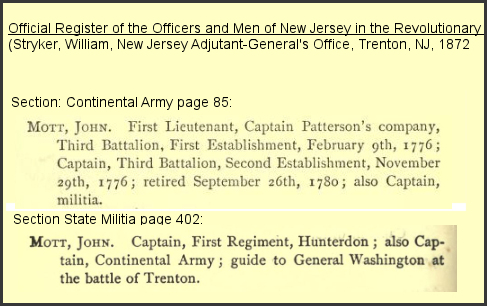

As Mr. Kidder points out in his article, the confusion

stemmed from Stryker’s Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War published in 1872. Mr. Kidder, the eminent historian of Trenton, has produced, among other books and

articles, two significant books researching original records of militia units, Crossroads of the Revolution, Trenton 1774-1783 and

A People Harassed and Exhausted – The Story of a New Jersey Militia Regiment in the American Revolution.

It is in the latter that the story of Captain John Mott of the 1st Hunderdon Militia Regiment unfolds.

This John Mott lived just north of Trenton on the River Road on a 165-acre farm about where the Trenton Country Club is today,

and he was most certainly the man who guided Washington at the Battle of Trenton.

As Mr. Kidder points out in his article, the confusion

stemmed from Stryker’s Official Register of the Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War published in 1872. Mr. Kidder, the eminent historian of Trenton, has produced, among other books and

articles, two significant books researching original records of militia units, Crossroads of the Revolution, Trenton 1774-1783 and

A People Harassed and Exhausted – The Story of a New Jersey Militia Regiment in the American Revolution.

It is in the latter that the story of Captain John Mott of the 1st Hunderdon Militia Regiment unfolds.

This John Mott lived just north of Trenton on the River Road on a 165-acre farm about where the Trenton Country Club is today,

and he was most certainly the man who guided Washington at the Battle of Trenton.

While Kidder’s blog was posted in 2011 it took me a number of years to finally document “my" John Mott. While the militia Captain Mott was from Trenton and the guide to Washington,

the regular army John Mott, my ancestor, was from Mount Holly.

Mount Holly, New Jersey is some 15 miles, as the crow files, south of Trenton in Burlington

County, and 19 miles east of Philadelphia across the Delaware river. Documents on hand or online leave no doubt: his father’s purchase of

land there in 1754, his will of 1770 leaving the property to his son John, records of the Quaker meetings listing children, removals

and those disunited, and the tax rate tables are among the many records. While I’ve never been able to pin down exactly where his land was,

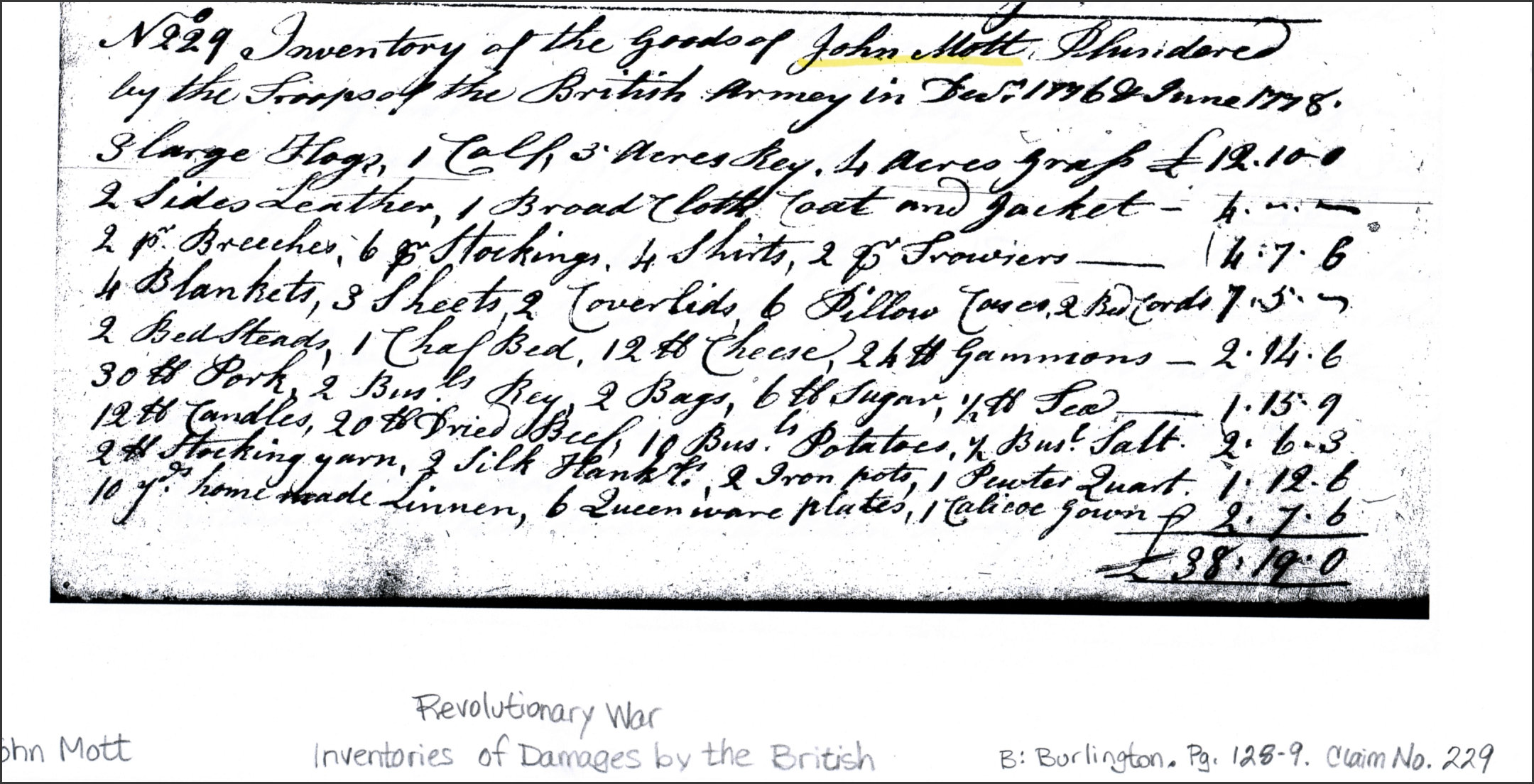

it seems likely that it was just north and west of Mount Holly. One clue to that is in the Revolutionary War Damage Claims, 1776-1782 done

by the State.

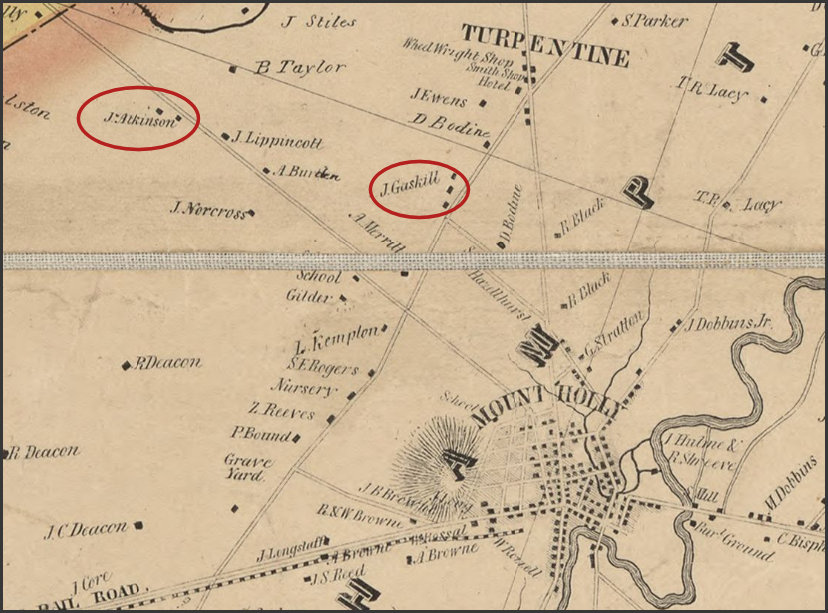

John’s claim, number 229, was witnessed by Job Atkinson, whose claim, number 226, was witnessed by John.

John also witnessed the claim of John Gaskill whose brother Daniel was married to John’s sister Hulda; John’s father, Ebenezer Mott,

had bought, in 1754, his land from James Gaskill. A much later map, 1849, identifies both J. Gaskill and J. Atkinson, no doubt descendants,

as having homesteads north and west of Mount Holly. Also, in 1782 there is a record of John having sold

approximately 2 ¼ acres to one Axel Harker and his wife.

John’s claim, number 229, was witnessed by Job Atkinson, whose claim, number 226, was witnessed by John.

John also witnessed the claim of John Gaskill whose brother Daniel was married to John’s sister Hulda; John’s father, Ebenezer Mott,

had bought, in 1754, his land from James Gaskill. A much later map, 1849, identifies both J. Gaskill and J. Atkinson, no doubt descendants,

as having homesteads north and west of Mount Holly. Also, in 1782 there is a record of John having sold

approximately 2 ¼ acres to one Axel Harker and his wife.

While the damage claims identify damages done in December, 1776, and June, 1778, what Amanda Jones wrote that “One bitterly cold Sunday in December, 1776, John Mott was

forced to defend his family…” is clearly in error in that, as we shall see, John was many miles away in New York State. That does not negate that his property was

violated in 1776, for the British occupied Mount Holly with heavy fighting north of town on Christmas Eve. An article in the Journal of the American Revolution,

Engagement at Woodlane details this, the prelude to the Battle of Iron Works Hill at Mount Holly around Christmas, 1776.

We shall see later the occupation of Mount Holly in 1778.

Whatever and whenever damage occurred to John’s homestead and family, throughout the Revolution much of New Jersey was subject to the ravages of troops from both sides as well as

deserters and robbers.

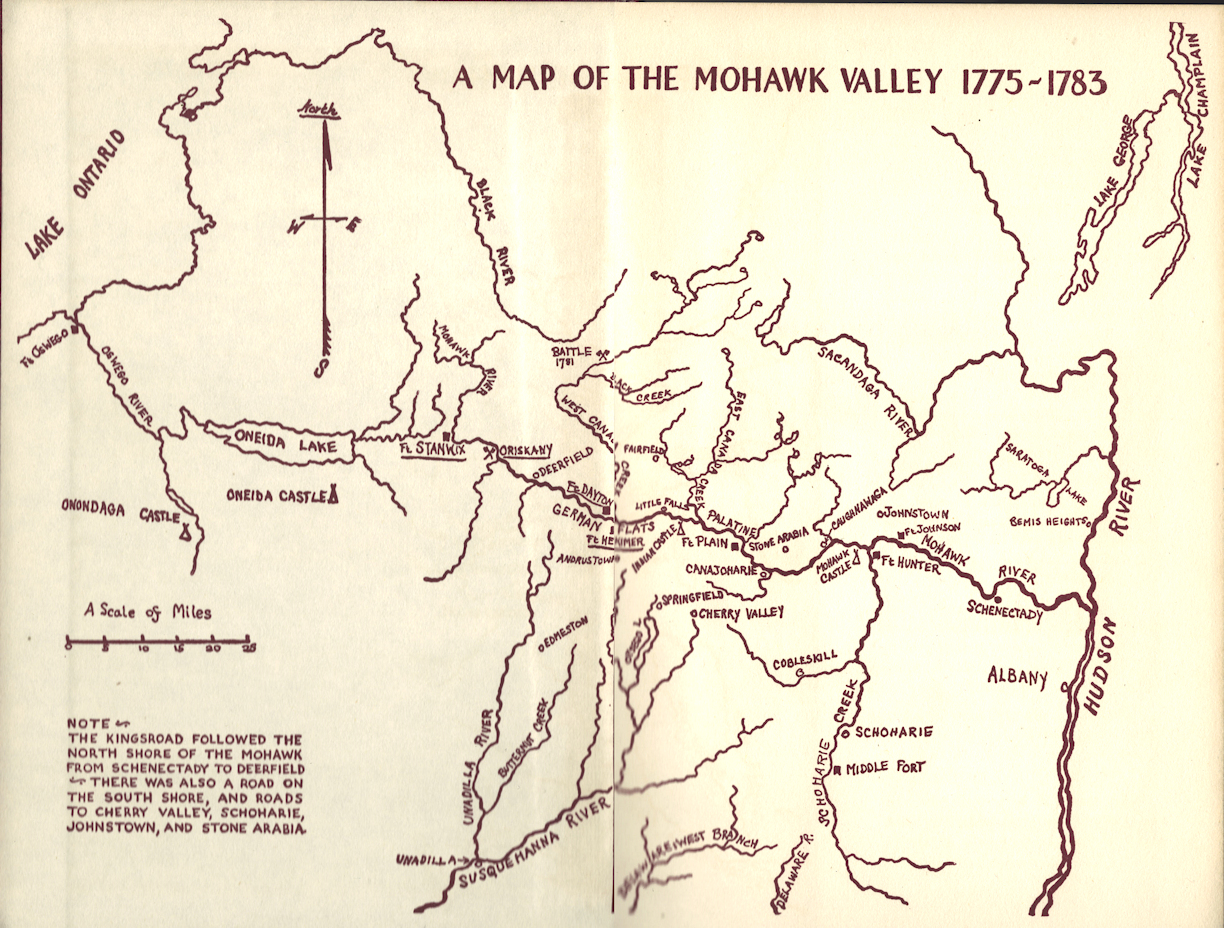

Two days before the Declaration of Independence was read to the public Lieutenant Mott of the Third New Jersey Battalion sat near the banks of the Mohawk River in

central New York State drinking a toddy with Ebenezer Elmer, his battalion’s surgeons’ mate. They were at German Flats where work was beginning on fortifying

what was come to be known as Fort Dayton.

This episode was featured in the first part of the highly popular but fictionalized 1939 movie “Drums Along the Mohawk.”

Things were tense. Many of the Scots-Highlanders and Dutch

settlers were British Tories and the loyalties of the Indians were divided.

Two days before the Declaration of Independence was read to the public Lieutenant Mott of the Third New Jersey Battalion sat near the banks of the Mohawk River in

central New York State drinking a toddy with Ebenezer Elmer, his battalion’s surgeons’ mate. They were at German Flats where work was beginning on fortifying

what was come to be known as Fort Dayton.

This episode was featured in the first part of the highly popular but fictionalized 1939 movie “Drums Along the Mohawk.”

Things were tense. Many of the Scots-Highlanders and Dutch

settlers were British Tories and the loyalties of the Indians were divided.

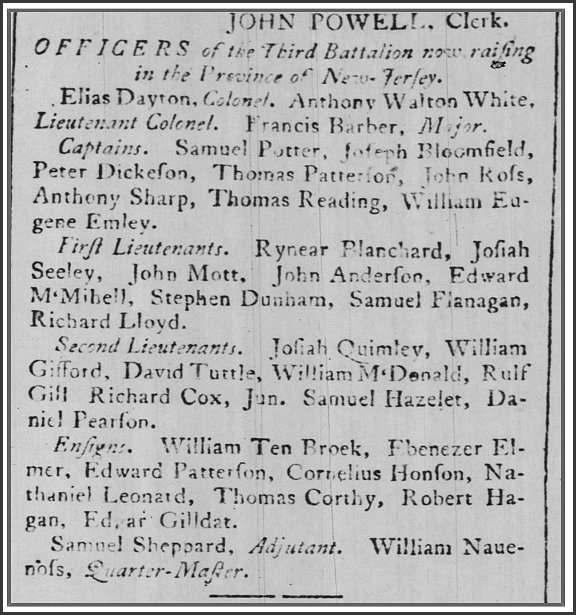

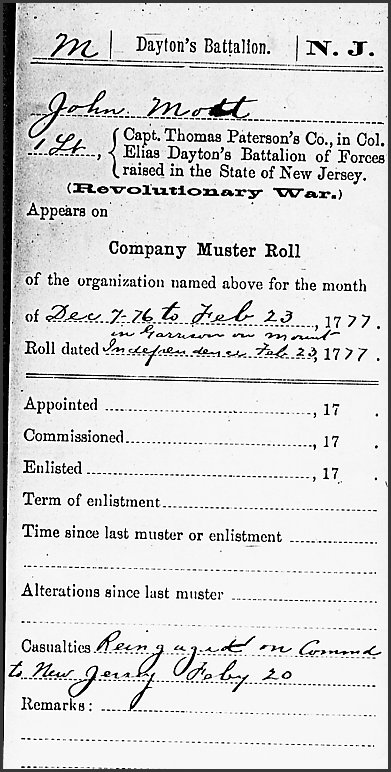

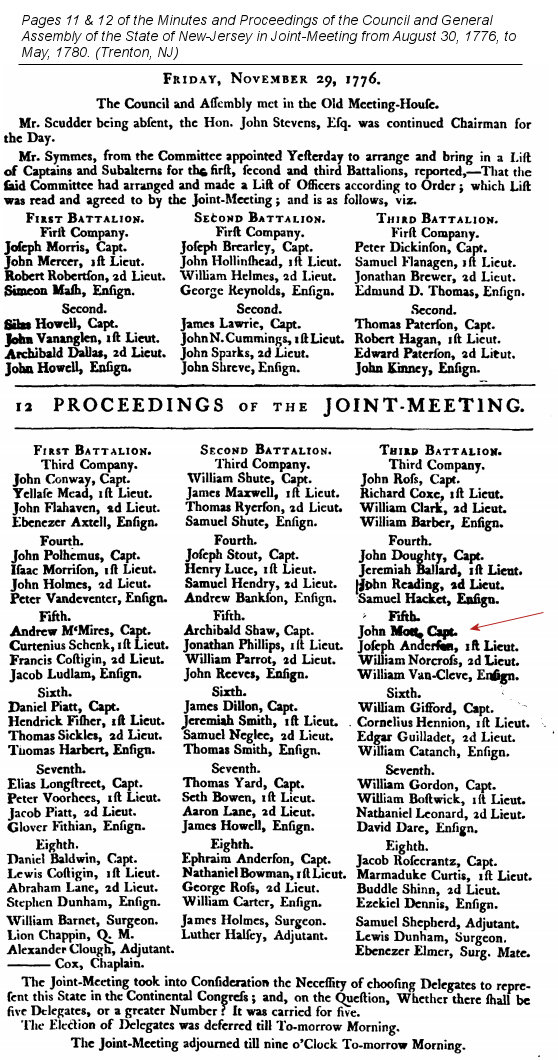

Five months earlier Lt. Mott had been commissioned First Lieutenant in the second company of Elias Dayton’s Third Battalion.

The company, that of Captain Thomas Patterson, had organized and left

from New York City with the battalion after being addressed by General Washington as “…the flower of all the North

American forces.” Sailing north on the Hudson on May 3rd they were to meant to bolster the campaign against the British in Canada,

a campaign that was failing disastrously even as they sailed. Arriving at Albany on the 9th, the situation had changed.

Albany, and the Hudson, was vulnerable to British attack from the north, but too it was vulnerable from attack from the west down the

Mohawk. General Philip Schuyler, in charge of the army’s Northern Department, ordered Dayton’s battalion west.

Five months earlier Lt. Mott had been commissioned First Lieutenant in the second company of Elias Dayton’s Third Battalion.

The company, that of Captain Thomas Patterson, had organized and left

from New York City with the battalion after being addressed by General Washington as “…the flower of all the North

American forces.” Sailing north on the Hudson on May 3rd they were to meant to bolster the campaign against the British in Canada,

a campaign that was failing disastrously even as they sailed. Arriving at Albany on the 9th, the situation had changed.

Albany, and the Hudson, was vulnerable to British attack from the north, but too it was vulnerable from attack from the west down the

Mohawk. General Philip Schuyler, in charge of the army’s Northern Department, ordered Dayton’s battalion west.

Their mission was threefold. They were to secure (capture) Sir John Johnson, the infamous Tory son of Sir William Johnson who had died in 1774 but had had the favor the

Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. Secondly they were to treat with the Indians, and after two days of conferences, May 20th and 21st, Dayton had convinced

the warriors that no harm would come to them provided they did not take the side of the British in the white man’s “family quarrel.”

The third part of their mission would take the rest of the summer into the fall.

While his friend Ebenezer Elmer remained the rest of the summer at Fort Dayton, it seems evident that John, with his Company, would go

even further up the river to Fort Stanwix, which they renamed Fort Schuyler, and begin work on restoring the fort which would be

critical the following year in repulsing a British attack from the west.

On October 12th Lt. Mott, along with the entire battalion, was ordered to return to Fort Ticonderoga. With the defeat of Benedict Arnold’s

navy on Lake Champlain at the Battle of Valcour Island on the 11th, the powers to be became fearful of a renewed British attack from the

north and Fort Ticonderoga, and Mount Independence just across the narrows, were in need of fortification. Sir John Johnson had fled west

even before the conference with the Indians and was not a threat for the time being. The next summer's fighting in the Mohawk valley would, however,

be some of the bloodiest and violent of the Revolution.

John and the troops garrisoned the winter of 1776-1777 at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence would endure conditions that rivaled,

or exceeded, the more famous encampment a year later at Valley Forge. Very cold air came mid-November, the lake froze over, the bridge

over the lake connecting the two outposts got blown away by wind and ice on December 14th, and a storm on Boxing Day left snow knee deep.

Michael Barbieri’s excellent article, Winter Soldiering in the Lake Champlain Valley details those conditions more fully and

compares them to Valley Forge the next year. John was sick in the barracks when the muster roll was taken on the 6th of December.

Joseph Bloomfield, whose journal as Captain of the seventh company is so valuable, had taken sick on the 29th of November and remained

so until he left for the Jerseys on Christmas day. On December 21 Ebenezer Elmer, himself sick, wrote that the “Regiment in general very

sickly. Scarcely a day passes but some one dies out of it.”

John and the troops garrisoned the winter of 1776-1777 at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence would endure conditions that rivaled,

or exceeded, the more famous encampment a year later at Valley Forge. Very cold air came mid-November, the lake froze over, the bridge

over the lake connecting the two outposts got blown away by wind and ice on December 14th, and a storm on Boxing Day left snow knee deep.

Michael Barbieri’s excellent article, Winter Soldiering in the Lake Champlain Valley details those conditions more fully and

compares them to Valley Forge the next year. John was sick in the barracks when the muster roll was taken on the 6th of December.

Joseph Bloomfield, whose journal as Captain of the seventh company is so valuable, had taken sick on the 29th of November and remained

so until he left for the Jerseys on Christmas day. On December 21 Ebenezer Elmer, himself sick, wrote that the “Regiment in general very

sickly. Scarcely a day passes but some one dies out of it.”

On the 16th of January the whole garrison assembled to hear the news of the victory at Trenton, and 10 days later, on the 26th Lt. Mott

learned that he was now a Captain, having been commissioned such the previous month by the New Jersey Legislature.

He must have made somewhat of a recovery from whatever ailed him, for on

February 9th he commanded a scouting trip, returning on the 11th “without any discover.”

On the 22nd Ebenezer Elmer wrote that “…the men died so fast for some time that the living grew quite wearied in digging graves for the

dead in this rocky, frozen ground.” Two days before he wrote that, however, the now Captain Mott may have left for New Jersey as the muster roll for

the 23rd says “Reingaged. On commd, to New Jersey Feb 20.” On the 28th the Third New Jersey was ordered off duty and after a march of

20 days was discharged at Morristown, New Jersey with pay and 20 days furlough. The First Establishment of the New Jersey Line was now

gone, dissolved at Morristown where General Washington had taken winter quarters and was busy consolidated his ragged army.

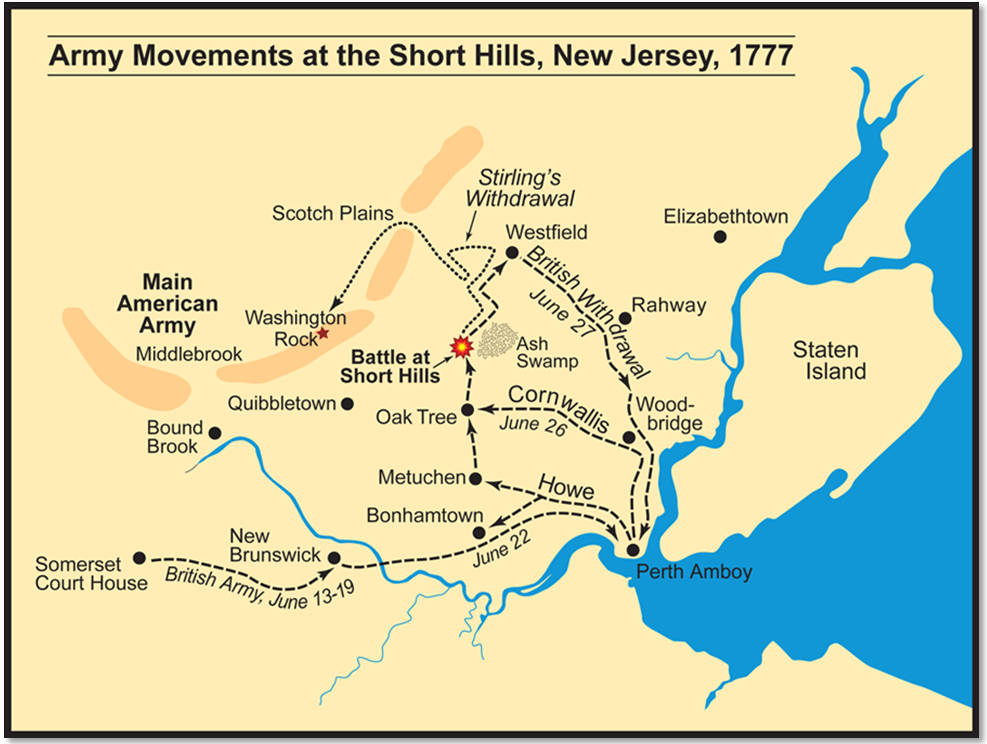

Now a Captain in Elias Dayton's battalion, John reported for duty in April of 1777 and participated in the battles and skirmishes in eastern New Jersey,

the June 26th Battle of Short Hills in particular, when British General Howe made a feint into New Jersey hoping to draw Washington into a major battle.

Washington wasn’t fooled; Howe boarded his ships and sailed south to then come up the Delaware River to attack and occupy Philadelphia, the rebel capital.

Now a Captain in Elias Dayton's battalion, John reported for duty in April of 1777 and participated in the battles and skirmishes in eastern New Jersey,

the June 26th Battle of Short Hills in particular, when British General Howe made a feint into New Jersey hoping to draw Washington into a major battle.

Washington wasn’t fooled; Howe boarded his ships and sailed south to then come up the Delaware River to attack and occupy Philadelphia, the rebel capital.

Raids and skirmishes by both the British and the Colonials continued across the narrow river between Staten Island

and New Jersey, all the way from Perth Amboy north to Elizabethtown. In reprisal for a raid by the British on Woodbridge, NJ, Colonel Dayton’s battalion was among

those ordered over to Staten Island where they secured captives and prizes on August 22. At the end of August the battalion marched south through Philadelphia to join

Washington’s whole army at Wilmington, Delaware. New Jersey was truly the “Crossroads of the Revolution,” and this map shows the extent of that.

Raids and skirmishes by both the British and the Colonials continued across the narrow river between Staten Island

and New Jersey, all the way from Perth Amboy north to Elizabethtown. In reprisal for a raid by the British on Woodbridge, NJ, Colonel Dayton’s battalion was among

those ordered over to Staten Island where they secured captives and prizes on August 22. At the end of August the battalion marched south through Philadelphia to join

Washington’s whole army at Wilmington, Delaware. New Jersey was truly the “Crossroads of the Revolution,” and this map shows the extent of that.

Washington had moved to protect Philadelphia and John joined in the principal Battles of Brandywine and Germantown. The payrolls and muster rolls for this period lack a location. However, Captain Mott’s participation in

these battles is verified by, among others, Private James Ray, whose name appears on all of Mott’s payrolls from February/May, 1777 to December, 1778,

and whose pension papers legally depose that he served in Mott’s company and fought at the battles of Short Hills, Brandywine, Germantown in 1777,

and Monmouth Court House in June of 1778.

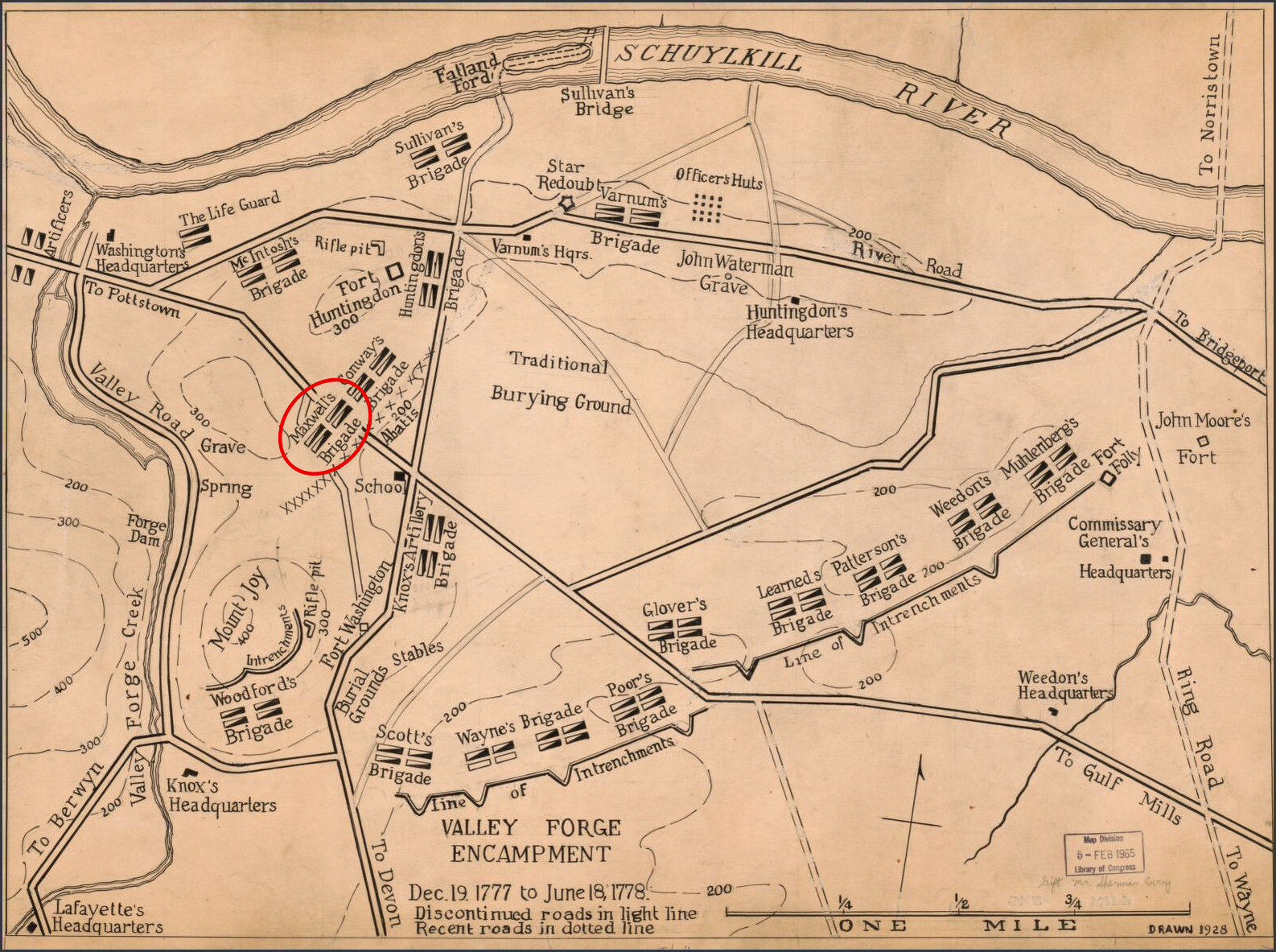

While the British occupied Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-78, John joined his mates in Valley Forge in December. By then all four battalions of the New Jersey line had

come under the leadership of General William Maxwell, known as “Maxwell’s Brigade.” He likely missed most of the

brutal conditions of camp for in the December payroll his Lieutenant, Mahlon Ford, is noted as “commanding the company,” and on the next two payrolls, January and February,

it is indicated that he was on furlough, perhaps with his family in Mount Holly, some 35 miles due east as the crow flies.

While the British occupied Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-78, John joined his mates in Valley Forge in December. By then all four battalions of the New Jersey line had

come under the leadership of General William Maxwell, known as “Maxwell’s Brigade.” He likely missed most of the

brutal conditions of camp for in the December payroll his Lieutenant, Mahlon Ford, is noted as “commanding the company,” and on the next two payrolls, January and February,

it is indicated that he was on furlough, perhaps with his family in Mount Holly, some 35 miles due east as the crow flies.

In March and April Captain Mott was present with his company at Valley Forge per the muster rolls. Washington knew that the British were about to abandon Philadelphia, but did not know what route they would take back to New York City. In May he was fairly sure that they would take the

shortest route, through Mount Holly and central New Jersey. On May 25th he instructed General Maxwell to take his brigade and join the militia units of militia General Philemon Dickinson

to position themselves in New Jersey to harass the British retreat. In his May 29th letter to General Maxwell he wrote, “you are, as before directed, in conjunction with the Militia, to break up and

obstruct the Roads, and make their march as difficult as possible.” This is why we find Captain Mott’s company mustered at Mount Holly on June 12th. Also mustered there that day was Captain Isaac Morrison’s company, about whom we will hear more about later. John is, however, listed as ‘sick / absent” as are several others in his company who are either “sick / absent” or “on comm’d.”

On June 9th, the British began crossing the Delaware with a 12-mile long procession which along the way plundered everything they could find, from household goods to livestock.

On June 20th the British paused at Mount Holly for two days, burning the iron works and the home of Colonel Shreve, the commander of the 2nd New Jersey battalion.

Another record from this time is in the Quaker “Record Book of Sufferings” which names John as a ‘constable’ having appropriated a horse and some lumber.

Washington took the main army out of Valley Forge, moved north and then east to intercept the British at Monmouth Court House, a battle in which John and his company participated.

Monmouth, one of the longest and hardest fought

engagements of the war, showed that American troops, now well-trained, could stand up in open field combat against the best the British had to deploy.

On June 9th, the British began crossing the Delaware with a 12-mile long procession which along the way plundered everything they could find, from household goods to livestock.

On June 20th the British paused at Mount Holly for two days, burning the iron works and the home of Colonel Shreve, the commander of the 2nd New Jersey battalion.

Another record from this time is in the Quaker “Record Book of Sufferings” which names John as a ‘constable’ having appropriated a horse and some lumber.

Washington took the main army out of Valley Forge, moved north and then east to intercept the British at Monmouth Court House, a battle in which John and his company participated.

Monmouth, one of the longest and hardest fought

engagements of the war, showed that American troops, now well-trained, could stand up in open field combat against the best the British had to deploy.

While the May, June, and July, 1778 muster rolls show him as “sick absent”, starting in August Captain Mott was with his company garrisoned at Elizabethtown, no doubt dealing with Tories and threats of raids from Staten Island.

His granddaughter, Amanda T. Jones, wrote, “…[he] was much employed by Washington in secret service. He, himself, related to my mother (then a child of nine),

the story of his pursuit and capture of a spy who was carrying important papers to the British.” This could very well have happened in the months following Monmouth

when in Elizabethtown that he was so “employed”; his Colonel had been charged by Washington to keep track of British movements and had been doing so since the

summer of 1777.

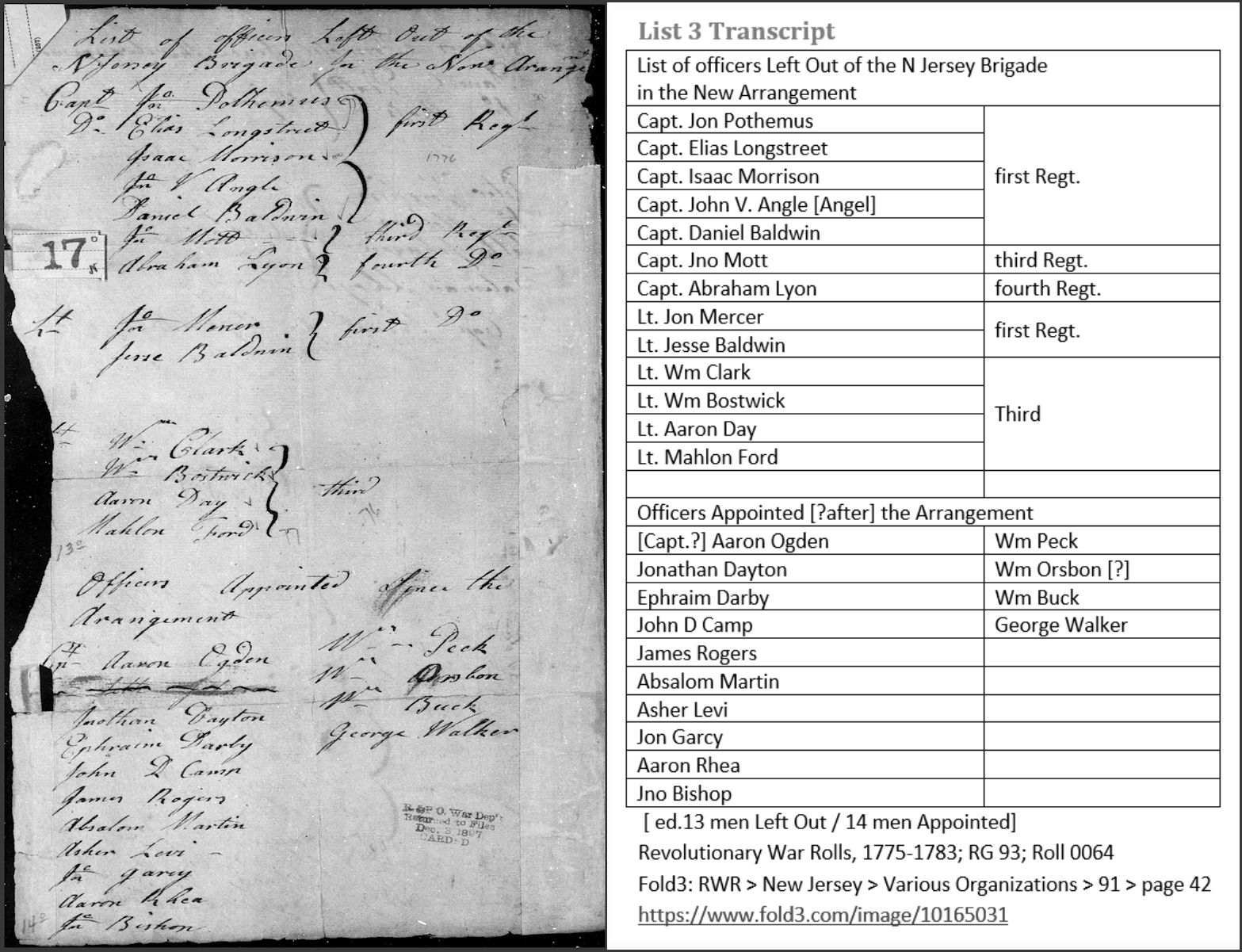

In January or February of 1779 Captain Mott lost his company. The muster roll for February taken at Elizabethtown on the 23rd of March has much of his company,

from First Lieutenant Nathaniel Leonard to Private James Ray and others, now under the command of Major Conway. John had been unwillingly relieved of duty, declared a supernumerary.

Dated April 21, 1779, John was one of four signatories of a letter to the Governor and General Assembly of New Jersey.

The four, along with a handful of others, had been made supernumerary and paid off in February and their complaint was that the army,

or the “Confederation of the United States,” had no authority to do so given that they had received their commissions from the State of New Jersey.

The full letter transcribed is in the Appendix to this article. It was a messy time, that late winter and spring of 1779, as the army was

stretched for money and units were consolidated; the 4th New Jersey regiment was dissolved and many of its officers transferred to the 1st New Jersey.

There may have been another reason why these men were paid off though, and the key to this lies with one of the four signatories, Isaac Morrison.

Morrison had brought charges against his Colonel, Matthias Ogden, which led to Ogden’s court martial in March. In a letter to the commander of the

New Jersey regiments, Brigadier General William Maxwell, General Washington wrote, “Capt. Isaac Morrison has lodged some charges of a very high nature

against Colo. Ogden…I think myself under the necessity of having the matter enquired into.” The trial of Matthias Ogden has been closely examined by one of

his descendants in a series of blog articles and there is no reason to go into it here, other than to say that of the four charges, neglect of duty, repeated frauds,

cowardice, and gaming were all dismissed save gaming, or gambling with enlisted men, something that Washington had seriously discouraged from the onset of

his command. While three of the signers of the letter to Governor Livingston, Elias Longstreet, John Polhemus, and Morrison,

were involved in the trial, Captain Mott was not. I am certain that he was friends with Morrison and that may have had something to do with his being paid off,

declared a supernumerary.

There may have been another reason why these men were paid off though, and the key to this lies with one of the four signatories, Isaac Morrison.

Morrison had brought charges against his Colonel, Matthias Ogden, which led to Ogden’s court martial in March. In a letter to the commander of the

New Jersey regiments, Brigadier General William Maxwell, General Washington wrote, “Capt. Isaac Morrison has lodged some charges of a very high nature

against Colo. Ogden…I think myself under the necessity of having the matter enquired into.” The trial of Matthias Ogden has been closely examined by one of

his descendants in a series of blog articles and there is no reason to go into it here, other than to say that of the four charges, neglect of duty, repeated frauds,

cowardice, and gaming were all dismissed save gaming, or gambling with enlisted men, something that Washington had seriously discouraged from the onset of

his command. While three of the signers of the letter to Governor Livingston, Elias Longstreet, John Polhemus, and Morrison,

were involved in the trial, Captain Mott was not. I am certain that he was friends with Morrison and that may have had something to do with his being paid off,

declared a supernumerary.

There seems to be more here than meets the eye. Suspicions of nepotism and retribution can come from different interpretations of what is known.

The Ogdens and Daytons were close; Hannah, the daughter of Captain Mott’s Colonel, Elias Dayton, was married to Colonel Matthias Ogden.

Two of the men elevated in rank with the re-arrangement of commands and units were Dayton’s son and brother, Jonathan and Aaron respectively;

both were certainly worthy of the promotion. The best examination of the whole mess is in Timothy Abbott’s blog, The Court Martial of Matthias Ogden.

Part VI examines the socio-economic status and seniority factors.

Whatever really happened, an unhappy Captain Mott was no longer a Captain, no longer in the army as of February, 1779. Neither he nor any of his descendants ever

applied for a pension.

The day before Christmas, 1782, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported that John, along with two other men from Mount Holly,

took into custody one Kemble Stackhouse, a young white man, and four other men, negro refugee slaves, and jailed them in Burlington.

They were subsequently moved to Philadelphia, where three of the men were hanged for robbery in February of 1783

despite the pleas of Stackhouse’s mother. Public executions were fairly common at the time, but thankfully the

sentence for robbery was reduced from execution in 1786.

The day before Christmas, 1782, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported that John, along with two other men from Mount Holly,

took into custody one Kemble Stackhouse, a young white man, and four other men, negro refugee slaves, and jailed them in Burlington.

They were subsequently moved to Philadelphia, where three of the men were hanged for robbery in February of 1783

despite the pleas of Stackhouse’s mother. Public executions were fairly common at the time, but thankfully the

sentence for robbery was reduced from execution in 1786.

His granddaughter, Amanda T. Jones, wrote, “The country, after the war, was overrun with desperate men; and my grandfather was chosen County Sheriff,

to hold them in restraint…he organized a search-party, caused the glen to be surrounded and arrested the three…my grandfather labored hard to get his

sentence (Stackhouse) commuted.” A rather apocryphal description of a documented event, I've found no evidence that he was “chosen County Sheriff.”

In any case John was at home in Mount Holly, picking up the pieces of his shattered family and homestead.

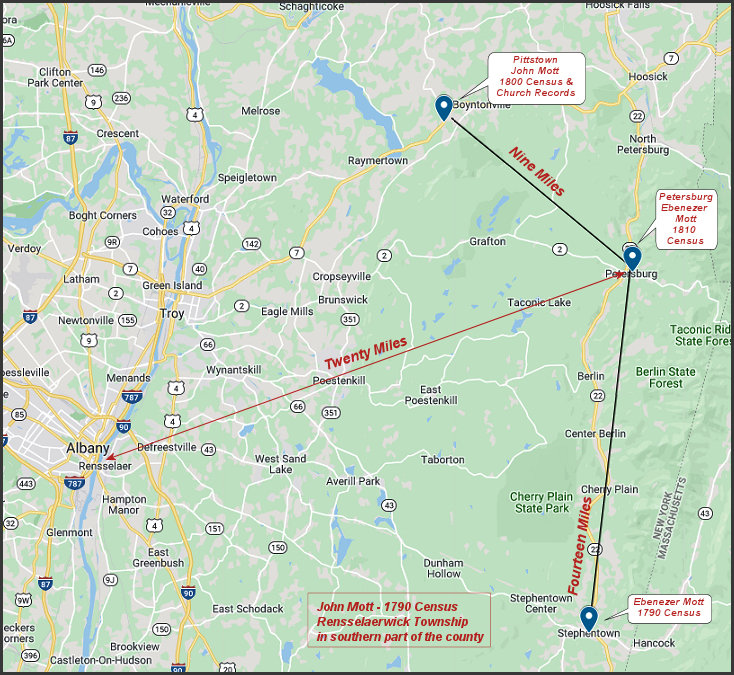

Exactly when or why John left for New York State is not known for sure, although it occurred before 1790 when he appears on the census of Rensselaerwick Township.

As to why, an educated guess is that having run out of resources to raise a family in New Jersey he went to live with, or near, his older brother, Ebenezer.

John did not stay long in southern Rensselaer County, drawn 20 miles north to Pittstown by something, or someone, namely Miss Naomi Daggett,

twenty-three years his junior. Naomi, along with her father, Mayhew Daggett, were among the founding members of the Pittstown Baptist Church in 1787 after moving to

Pittstown from Rhode Island following the death of her mother. On July 15, 1793 John was baptized and received as a church member in full communion in that church.

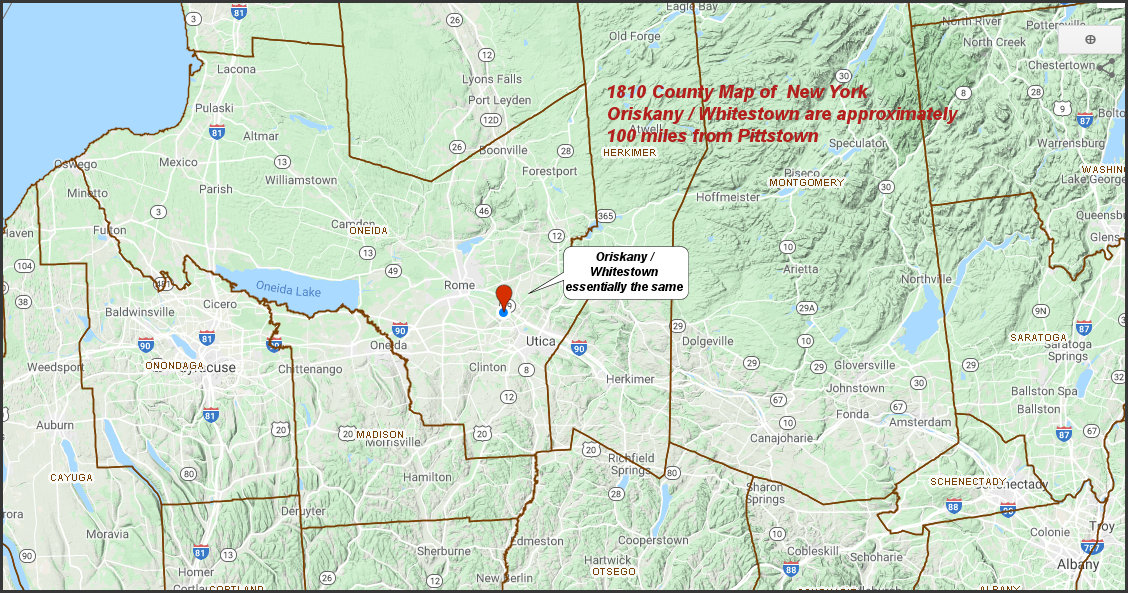

He served as its clerk until about 1808 when the family moved west up the Mohawk River into country he was familiar with from his time in the army in 1776.

While there are about 12 references to him in the church records, the last is this entry: “Brother Mott and Naomi his wife Reec’ed letter October the 10 1808.”

Exactly when or why John left for New York State is not known for sure, although it occurred before 1790 when he appears on the census of Rensselaerwick Township.

As to why, an educated guess is that having run out of resources to raise a family in New Jersey he went to live with, or near, his older brother, Ebenezer.

John did not stay long in southern Rensselaer County, drawn 20 miles north to Pittstown by something, or someone, namely Miss Naomi Daggett,

twenty-three years his junior. Naomi, along with her father, Mayhew Daggett, were among the founding members of the Pittstown Baptist Church in 1787 after moving to

Pittstown from Rhode Island following the death of her mother. On July 15, 1793 John was baptized and received as a church member in full communion in that church.

He served as its clerk until about 1808 when the family moved west up the Mohawk River into country he was familiar with from his time in the army in 1776.

While there are about 12 references to him in the church records, the last is this entry: “Brother Mott and Naomi his wife Reec’ed letter October the 10 1808.”

We know the dates that John and Naomi died from the family Bible; as to where, no conclusive records have been found. Many maintain he died in Bridgewater,

Oneida County, but this is the result of a confusion with another John Mott who was buried in that town, a completely different family.

There were at least twenty-three men by the name of John Mott in the State of New York in 1820, but I am confident that he is the one in Whitestown, Oneida County

which is likely where he, and possibly Naomi, died.

We know from the Family Bible that John and Naomi’s first child, Mayhew, was born in Pittstown in 1795; by the censuses, their seventh child, Theodocia was born in

Oneida county in August of 1808, and their last, Mary Alma, was born in Oriskany, Oneida County, New York, in February of 1813. John Mott appears on the 1820

census of Whitestown as a family of five persons. John’s son, Mayhew, was drafted into the New York Militia at Whitestown in 1814.

Three sons, Mayhew, John Jr, and Lemuel, appear on the 1830 census of Whitestown, as does the youngest daughter, Mary Alma, having married Henry Jones in 1828 when she was fifteen.

Lemuel Mott and John, Jr. appear next to each other in the 1830 census, Lemuel with only himself and one female, 60-69, who must be Naomi.

Amanda T. Jones, wrote, “At three we (1838 - Amanda was born in 1835) were visited by my grandmother Mott, whose beautiful, white face filled me with wonder.”

Three sons, Mayhew, John Jr, and Lemuel, appear on the 1830 census of Whitestown, as does the youngest daughter, Mary Alma, having married Henry Jones in 1828 when she was fifteen.

Lemuel Mott and John, Jr. appear next to each other in the 1830 census, Lemuel with only himself and one female, 60-69, who must be Naomi.

Amanda T. Jones, wrote, “At three we (1838 - Amanda was born in 1835) were visited by my grandmother Mott, whose beautiful, white face filled me with wonder.”

So-far I have recorded some 300 descendants of John Mott. From the communications I’ve had over the years I know there are many more, and many more that I simply haven’t searched out

and recorded. Further research may fill in missing pieces of family history and his activities during and after the Revolution.